Recommendation: Childhood memories of late writer activist Lakshman

Late Kannada writer-activist Lakshman’s autobiography has the feel of a novel and one of the anecdotes describes a drinking session he had with his grandfather while he was still a very young boy

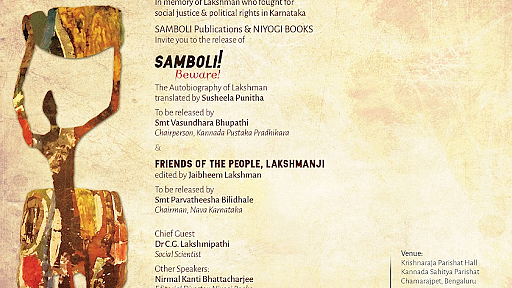

Lakshman’s memoir, Samboli! Beware!, translated from the Kannada original by Susheela Punitha, is a story of extreme poverty and despair. Lakshman was a Dalit, from the Madiga caste, and the book derives its title from an old practice of Dalits having to call out “Samboli!” – meaning “Beware!” – to warn others of their presence. The memoir has the feel of a novel and immediately grabs the attention of the reader in the opening lines itself.

“Amma had taken me to Gaanigarahalli near Banavara for the village festival to honour the gramadevathe, the Goddess of the village. It is the village of the Ganigas, the oil-presser caste, and Amma’s hometown; her parents lived there. During the festivities, I too ran across the smouldering embers in the devara konda, just as my ancestors had done before me; just as the other devotees were doing that day. After the festival, no one took me back home.”

Lakshman is raised by his grandparents, the parents of his mother, as his own parents were too poor to raise one more child. There is idyll and want going side by side in this part of the book. The house of Lakshman’s grandparents did not have any brick wall. The entire house was built of toddy-palm fronds, a strip of bamboo, and a rope. Yet, Lakshman calls this house “A Palace without Walls”.

One part that really appealed to me was the mention of Lakshman, a mere child, drinking alcohol with his grandparents.

“After the fair, we went straight to the Banavara toddy shop in the evening, bought two bottles of toddy and something to munch with it like chaakna, slices of mutton grilled on embers without any spices, and such savoury snacks as bonda or seasoned boiled beans served on leaves. We sat in the open maidan, calm and relaxed. We brought our palms together, bowing reverently to the toddy, and shared it with Mother Earth together with some of the eats before we let our hands and mouths fight with each other! Ajji gave me a sip of toddy from her bottle and then Thatha gave me a sip from his. The toddy was sour and tasty. We munched the chaakna and the other snacks with it.”

It would seem taboo for adults to have alcoholic drinks with children. Lakshman’s grandparents drinking with gay abandon and also sharing their drinks with their grandson is joyfully subversive.

Lakshman’s memories reveal a feeling of happiness even in deprivation. As a child, he brushed his teeth with some powdered brick, and what is more amazing than brushing teeth with powdered brick is the ease with which Lakshman recalls using powdered brick.

In some parts, the memory of wants is disturbing. In his childhood, it was common for Lakshman to beg.

“Countless Christians flock to the hill every year a week or two after Yugaadhi to pray at the cross on the grave. The way to that hill is a little beyond our slum. Soon after Yugaadhi, the children, the elders and the disabled from our colony await the return of the Christians, counting the days like the jaataka birds that swing upside down meditating on God. Because...on that day, the hands o our people jingle with coins—jana, jana.

“‘Swami, please give me three paise...three paise, Swami,’ I begged on that day from early morning, standing in the pathway to the grave or trailing the visitors, pulling a sad face with my palm stretched out. As soon as someone gave me some coins, I dropped them into the pocket of my shorts and went to another group and begged, ‘Swami, please, three paise...please...”

Apart from this, Lakshman worked as a coolie. But although begging and hard labour were normal for him, he was aware of the stigma attached to being a beggar and a coolie. He was always wary of his friends getting to know about what he did.

“‘God! Who else will see me working here as a coolie? When I go back to school, these boys will look at me and laugh among themselves, won’t they? God...!’ In my heart, I wept.”

Samboli! Beware! is the story of the struggle that a person from a lower caste wages against the oppressive caste system and the ways in which he inspires other people of lower castes to do the same. As such, there are several instances of logic trumping traditions. Upon being asked by his mother if he would offer ceremonial food on the graves of his parents in their memory, Lakshman says that he won’t as the food would have no use for his dead parents.

During a religious ceremony, when some people from a higher caste ask Lakshman to take a dip in water, Lakshman is hesitant as the shorts he were wearing were his only pair and he did not want those to get wet, even for gods and religion.

There is forthrightness and a childlike honesty and innocence in Lakshman’s words. This might be because most of the memories Lakshman recounts here are from his childhood. Written like a conversation, Lakshman’s Samboli! Beware! comes alive in Susheela Punitha’s translation and is an enriching read.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines