Book Review: Another look at Varanasi

Unlike Mecca or Jerusalem, Varanasi has been a thriving centre of arts, craft, trade and scholarship, and unlike several other coffee table books, this one is both insightful and readable

A 19th century British civil servant (Norman Mcleod) is credited with saying what Banaras is to the Hindus, Mecca is to Muslims and Jerusalem to Jews, a living embodiment of their religion. Varanasi, Kashi or Banaras, it is believed to be one of the seven major cities (Sapt Nagaris) which are timeless and settled by gods. Like all ancient cities that are both sacred and rich, Banaras also has a long record of socio-political upheavals, terror, violence, loot and bloodshed.

There is already an impressive body of literature on the holy city. Indian and foreign writers, scholars, travellers and priests have been writing for long about Kashi, the city of light, with a richly layered history stretching from the pre-historic times to the present. So, what’s new, one may well ask.

Here the coffee table format does injustice to the content, which with clear and logical precision sets out to reveal how the pilgrimage of Banaras Kshetra for at least two millennia, springs not from some evangelical revolution but is simply a cultural refuge inspired by the half magical trust of its forefathers and a way of life natural for the Kasheyas, denizens of Kashi.

The well-planned chapters present an intelligent and sensitive recapturing of the various tides of fortune the area has undergone from the Puranic ages through the Mughal rule to the present day. Its sacred geography, its rich earthy material connectionsand the centrality of the river Ganges to both the spirit and trade in Banaras. Having done that, it moves with effortless ease to peek into the quintessential Banarasiness of its lively inhabitants, the fabled Kasheyas in their daily lives as they work, bathe, worship, gossip, eat and negotiate the intricate web of lanes and by-lanes.

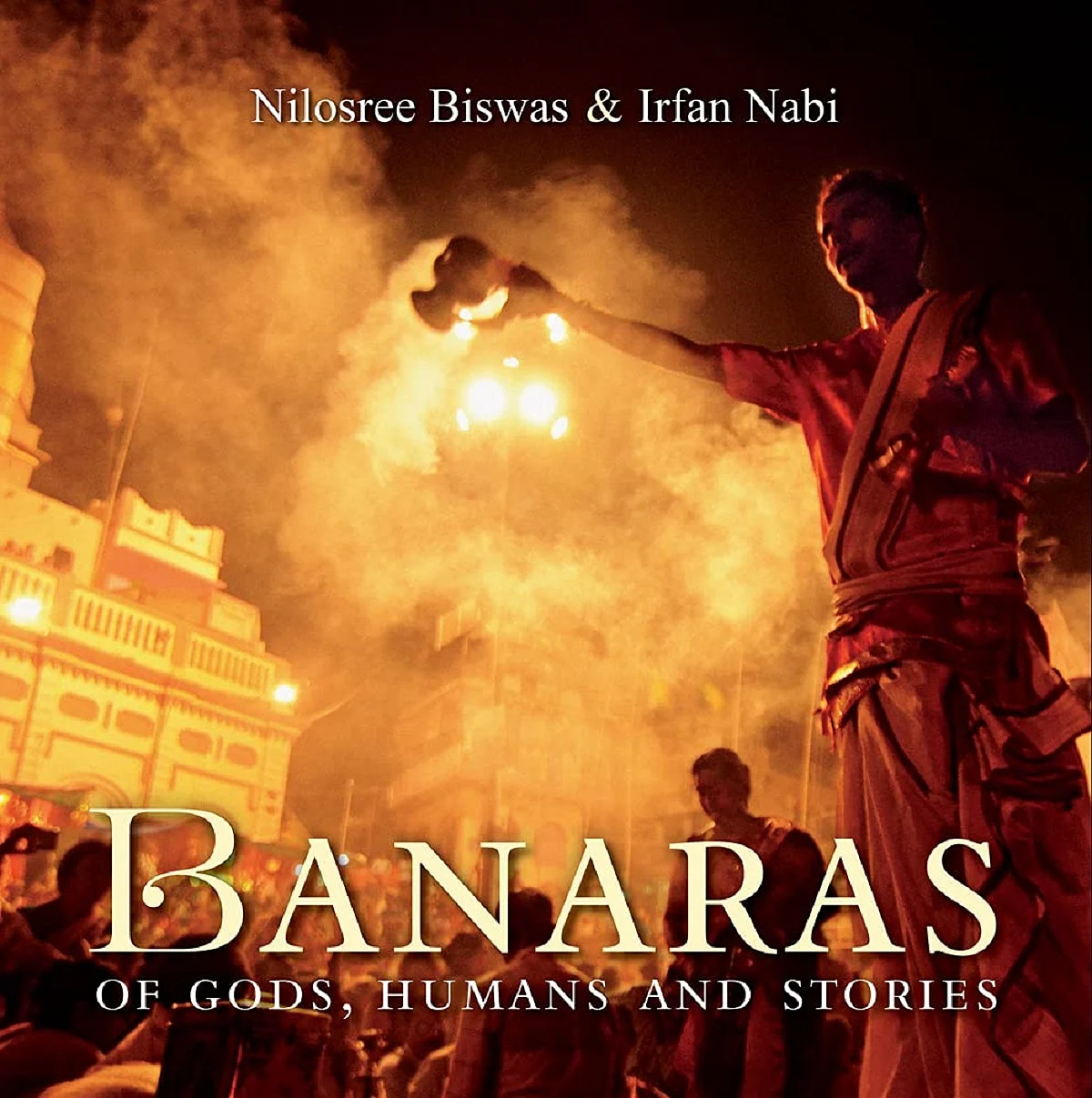

The book begins with a chapter on the sacred geography of the city where holiness overwhelms even a non-believer. Pilgrims and tourists alike take a dip in the water, chortling like children and carry the water home, like a bouquet, for the sick and the dying. Even death loses its sting as you watch the Aarti on the Ghats even as funeral pyres keep burning in the background.

Biswas realises it is not easy to understand the city. And it would be unfair to present it as a symbol for this or that, as many writers have done in the past. This is a holy city but is also a thriving centre of the arts and commerce. To circumvent this problem, the writer, as she moves along, keeps braiding together strands “of mythology, antiquity, informed imagination and a contemporary understanding of Banaras.”

The book moves easily from the Pauranic references into the regional and vernacular myths they have thrown up, to recorded history of the redevelopment of this city by various Mughal emperors from the egalitarian Akbar and the learned prince Dara Shikoh to the illiberal Aurangzeb. She has brought in testimonies of western travellers from the 16th century British traveller Ralph Fitch to the Frenchman Francois Tavernier to highlight the economic power of the area, where both Hindu and Muslim traders and craftsmen thrived.

If there is money and trade opportunities, can political machinery and masters stay detached? The chapter records the opulent gifts of land and money that the city received from its various benefactors, both Muslim and Hindu (Rajput and Maratha) rulers and rich moneylenders and Zamindars, which helped develop both holy sites and trade in the city.

These benefactors had one eye on the wealth and the higher learning the city generated, and another on its teeming and ethnically diverse population that worshipped at temples, mosques, graves of Sufi and Hindu saint poets, and lesser gods from a mixed pantheon of obsolete Naga and Yaksha deities. “Sometimes the narratives,” confesses Biswas, “may intersect with the present as the binding cement, but many times there may be two parallel running tracks that may move together...”

It is in this duality that for the humble pilgrim, subjected to politically crushing times and various deprivations, that the parallel world of a Moksha Nagari begins to make sense. All their aching weary flesh at last finds absolution in the lap of Maa Ganga.

The chapter on Ganges focuses on the allpervasive timeless flow of this vast river, whose healing, soothing and pure waters also nurse economic activities vital for the people of the area. As proof, Biswas refers here to a bevy of authors from Jagannath Prabhu and Bharatendu to James Prinsep and William Hodges, Danielle and art historian Havell who have recorded their own understanding of the city and the river with its Ghats.

From here the book dives deeper into the materialistic side of Banaras, the ancient hub for producing and trading in exquisite silks, wooden toys, Minakari, musical instruments and what have you. The chapter then makes a loop like Ganga to bifurcate and assess the world of the rich and the commoners in the city, showing how they developed over centuries, how today they continue to intersect yet have their own special place in the scheme of things.

Towards the end comes the description of Banarasipan, the typical and quirky Banarasi ‘attitude’. The unfettered bohemia of a city of gourmands, learning of the highest order, temple rituals and pandas, flower sellers, cremation ground staff, boatmen and paan sellers.

She describes the loquacious, good natured, lazy and yet astute and observant culture of the city of Shiva, a god who ‘owns’ the sacred area, the Avimukt Kshetra, the land where he first manifested himself as a pillar of light, a land that he told his spouse Parvati he shall never vacate. Biswas as closely as possible, has been able to capture in an alien language the halo and the mundane daily lives of this timeless city.

One only wishes the design of the book matched and adequately projected the very readable text within. The photographs of images of gods, men and animals in a riot of colours red, saffron and orange, have too often been seen on other coffee table books on Varanasi. What’s more, they seem to have been indifferently displayed here as a full page or as a square window cut into the text. This could have been done better. Unlike most coffee table books, however, it is meticulously researched and details are served without pompous speeches and explanations. It was good reading.

(The reviewer is the Group Editorial Advisor of National Herald)

(This article was first published in National Herald on Sunday)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

Published: 29 Dec 2021, 11:30 AM