The employment challenge: Race against time

PM Narendra Modi came in with a promise to solve India’s biggest crisis - creating jobs for our youth, he is ending his 5-year term with the largest number of unemployed, ever

In May of 2014, Prime Minister Narendra Modi presented himself as the leader with solutions to India’s complex problems. In January of 2019, he has reduced himself to a pale shadow of himself. He came in with a promise to solve India’s biggest crisis - creating jobs for our youth, he is ending his 5-year term with the largest number of unemployed, ever.

If anyone sat through the quota deliberations in the Lok Sabha on January 9, you would have wondered, is that all the Prime Minister has to offer? The bigger question, however, is that political slugfest aside, what do we need to do to create jobs for our young women and men?

We first need to understand how serious the problem has become. First time voters, people in the age group of 18-22, were a key voting segment for the BJP and Modi as they numbered 12.05 crore and made up roughly 14 per cent of the voters. The BJP swept through the Hindi heartland and other parts of the country with a message of hope, laced with the BJP’s usual communal agenda. Five years later, the message of hope is gone. The communal and divisive agenda of the BJP is the only thing that remains.

The job scenario in India resembles a scene out of a really scary, horror flick. CMIE data says that the total number of employed persons has fallen from 40.9 crore in December 2016 (four quarter moving average) to just over 40 crore. Over 90 per cent of these jobs are in the informal and unorganised sectors.

What is worse is that 1.1 crore jobs have been lost in 2018 and almost 90 per cent of these jobs were lost in rural India. A massive unemployed workforce, it seems, would be Modi’s legacy. In short, the jobs problem is not getting better, it is getting worse.

We are headed towards a much bigger problem, our demographic dividend is turning into a massive nightmare. If 12 crore Indians attaining working age in 2014 was a big number, consider this: the number is 13.08 crore in 2019 and 12.7 crore more are expected to attain the age of 18 years by 2024. By 2024, we would have about 45.25 crore who are going to be in the 18-35 age group. Will we be able to generate enough jobs for them? It is becoming a race against time.

On January 9 and 10, when the 124th Amendment was being discussed in both houses of Parliament, it was clear that the BJP does not understand how serious this problem is. Their half-baked solutions have not worked, and they know it. This is why they have tried to take a politically populist agenda to retain their core voter, rather than find long-term solutions to a serious national problem.

‘Make in India’ was marketed as the magic pill that would help create 10 crore jobs in the manufacturing sector by 2022 and make it 25 per cent of the GDP. With barely three years to go for the deadline to get over, the share of manufacturing in the GDP continues to dip and manufacturing now makes up only around 15 per cent of the GDP. The sector is not growing at the pace we want and hence manufacturing jobs have not come through.

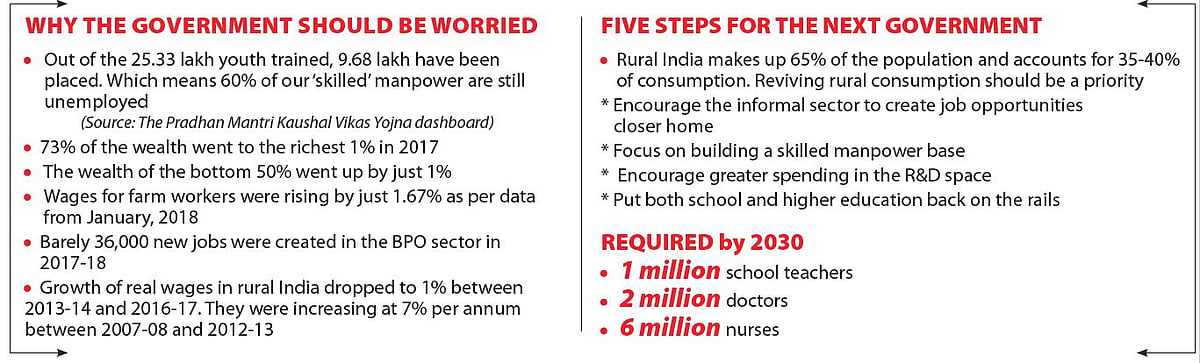

It was believed that India has an acute shortage of skilled manpower which was slowing us and ‘Skill India’ would bridge the gap. The reality is scary. The Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojna dashboard indicates that of the 25.33 lakh youth trained so far, 9.68 lakhs have been placed, or less than 40 per cent of the people have been employed, though CAG reviews in states like Rajasthan dispute these numbers. So, if 60 per cent of our ‘skilled manpower’ is still unemployed, we either have a skill gap or there are no jobs in the market.

While we can debate endlessly about what was wrong with the economic policies of the current government, it is important to start thinking about how we can fix it. For starters, we need to understand that there are no magic cures, the road to restoring job growth is going to be a long one but there are no shortcuts.

We need to create a jobs pyramid, large number of low-skill jobs at the bottom of the pyramid and some high-skill, high value jobs at the top which would add high value to our growth engine. We can’t leave one for the other because both are going to be critical in laying down a long-term economic growth paradigm.

The job creation policy has to focus on key areas-

* Boost consumer demand by ensuring bottom-up growth

* Encourage the informal sector to create job opportunities closer home

* Focus on building a skilled manpower base and

* Look at creating high technology jobs by encouraging greater spending in the R&D space.

The first step is to bring growth at the bottom of the pyramid which increases consumption in rural India. Domestic consumption is the mainstay of the Indian economy and it makes 60 per cent of our GDP and rural consumption is not growing because rural income is not growing, leading to higher income inequality.

As much as 73 per cent of the wealth went to the richest 1 per cent in 2017. The wealth of the bottom 50 per cent went up by just 1 per cent. Real wages in rural India were increasing at 7 per cent per annum between 2007-08 and 2012-13. This dropped to 1 per cent between 2013-14 and 2016-17 and data from January 2018 showed that wages for farm workers were rising by just 1.67 per cent.

After barely keeping pace with inflation in the first four years, the government did increase the MSP of farm produce, but the farmer continues to be hit as a large number of crops are being sold below MSP. We need to restore agricultural growth to ensure a revival of consumption.

Rural India makes up around 65 per cent of the population and accounts for around 35-40 per cent of the consumption and we will be able bring back job growth only when we revive rural consumption. In short, we need agriculture to grow at 4-5 per cent over the next two decades to achieve 8 per cent job-full growth.

We also need to expand social spending by increasing allocations to MGNREGA. The inflation-adjusted budget for 2018-19 is much lower than in 2010-11.

In 2010-11, the total allocation was Rs 40,100 crore which has been increased to Rs 55,000 crore in 2017-18 but after adjusting for inflation, this comes down to Rs 34,398 crore. This reduction has led to an acute cut in consumption by the people at the lowest end of the economic and social spectrum.

Improved farm economics and increased real spending on welfare schemes will help us kick-start bottom-up growth.

Congress president Rahul Gandhi had started work on the Shaktiman Food Park in his constituency and this is a model which needs to be taken up at national level.

The biggest challenge, however, is going to be on how we are going to shift rural youth to agri-services and rural manufacturing to expand avenues of non-farm rural employment.

We need to expand our food processing capabilities significantly and rapidly to ensure value addition to our crops, fruits, vegetables and milk. We need to set up a network of food processing parks across the country so that farm produce can be preserved, processed and marketed more efficiently, not only in India, but in the global market and this should be taken up at a rapid pace by providing energy linkages on a priority basis.

The informal manufacturing sector, small units which are driven by local demand, have been hit the hardest due to Demonetisation and this sector needs to be revived. While this sector would be revived once rural consumption grows, we need to empower the banking system to provide them with the financial support to ensure that they grow into companies in future. These are going to be our organic start-ups for the future.

The social services sector is expected to create massive employment opportunities. We are short by a million teachers in both elementary and secondary levels (2016) and we could significantly improve learning outcomes. Estimates suggest that India would need 2 million doctors and 6 million nurses by 2030.

We also need focus on high-end jobs. IT and ITES were one of the largest employers for India’s educated work force. Only 36,000 new jobs were created in the BPO sector in the 2018 fiscal. We need to retrain our technology sector workers if they are going to stay competitive in the job sector and make India a global hub for cutting edge work in IT.

India has obvious strengths in pharma and other high-technology sectors but our investments in R&D have been below 1 per cent over the last two decades and is half of what the Chinese spend. The government needs the revenue to keep the ship sailing but we need R&D investments for Indian companies to be competitive in the future, even if we have to provide some tax breaks.

Those who had promised magic cures to increased employment have failed to deliver. It is time that we get real and first have a plan to stop people from losing their jobs. It is important that we draw out long-term plans to put job creation at the top of our national political agenda. Or else, we can keep talking about issues that would divide us. We have three months to decide which road we plan to take.

This article first appeared in National Herald on Sunday.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines