Minimalist etchings of a crime tale

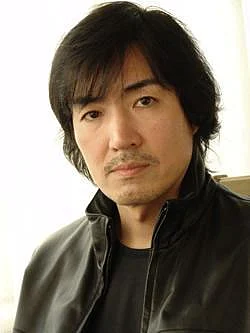

Keigo Higashino’s new novel falls broadly into the Police Procedurals although it has elements of a Whodunit as well

The genre of mystery fiction first came into mainstream consciousness around the 19th century. This was a century after the Industrial Revolution had changed the landscape of most of Europe. With development, also came crime, and the new wave of authors in this era were responding to the changing social realities through their novels. Of them the most prominent remain Edgar Allan Poe, Agatha Christie and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. They shaped the genre in their own way and have left a blueprint for future authors. In the 20th century, as the genre gained more popularity, it diversified into various sub-genres like Caper, Hardboiled, Espionage, Historical Crime, Legal Thrillers, Medical Thrillers, Police Procedurals, Whodunits and so on.

Keigo Higashino’s new novel Newcomer: A Story of Death in Tokyo falls broadly into the Police Procedurals although it has elements of a Whodunit as well. The story begins when Mineko Mitsui, a lady who has separated from her better half and as of late migrated to the Kodenmacho neighbourhood of Tokyo’s Nihonbashi locale, has been choked in her new apartment. The neighbourhood is suspicious of newcomers as it is. Agents from the neighbourhood area have collaborated with the Tokyo Metropolitan Police to unravel this incident, yet few pieces of crucial information present itself before them. They include: a deferred meeting with an old companion; a telephone call that the lady got before her passing; her stressed association with both her former partner who the leader of a cleaning organisation and her son who is an aspiring actor. The responsibility of solving the crime falls on Kyoichiro Kaga, himself a newcomer detective in the area. The theme of being a ‘newcomer’, a fresh ‘alien’ in a world of set rules, regulations and patterns runs throughout the novel. Satako, the matriarch of a shop selling rice-crackers and her son, Fumitaka, who is the current owner, often make spurious comments such as “the area’s not safe anymore, there are just too many newcomers.” To the same effect, they seem to jump to the conclusion of the victim’s fate: “Forty-five and living alone. It’s a little unusual not to be married at that age.” They do not consider the fact that due to Mitsui’s recent arrival, precise information is hard to find. Gradually we learn Mitsui has been divorced for six months, is estranged from her actor son and arrived in Nihonbashi to attempt a fresh start, working as a translator. This gap in understanding can also be seen as the new wave of Japanese socio-economic class of people causing tremors in a seemingly well laid-out social structure of the land.

Kaga, the compass of the story, is described as having a ‘razor-sharp mind and bloodhound nature.’ A former anti-hero of Higashino’s masterful The Devotion of Suspect X (2005), Kaga makes his appearance in this novel in a bar, albeit a Bond-esque manner. He asks for a drink but doesn’t bother to look into the menu. His appearance is plain, and unprofessional (a short-sleeved shirt over a T-shirt), belying his true identity. His methodology is also unorthodox, raising several questions with a highly orthodox community. A former member of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department’s Homicide Division, he was demoted to a precinct detective after a victim’s family made a formal complaint about the ‘investigator’s inappropriate’ emotional involvement. But Higashino portrays him as a seemingly detached person with scant time for wallowing in regret or for self-reflection. In doing so, he attempts to go for a Sherlock Holmes-esque poker coolness, but the payoff isn’t as smooth as Doyle’s sleuth probably because he has much more backstory to him. There are also overlapping similarities to Lisbeth Salander, the iconic creation of Stieg Larsson’s brilliant ‘Millennium Series’. However, unlike Salander, Kaga isn’t given much room to breath nor does he dig as deep as Salander who serves as a contemporary symbol of investigation into Sweden’s dark socio-economic-political-sexual corridors.

Dividing the structure of his novel into 9 chapters, each containing a self-contained story, with its own conflicts, its own resolution, and its own focus character, Higashino uses the setting of Nihonbashi as a labyrinth to uncover the mystery. Kaga gets all his clues from minor background details, highlighting the importance of ‘trivia.’ At one point in the novel he notes, “It’s an interesting district,” before offering a seemingly offhand but characteristically enthusiastic description of an “extraordinary clock” with three faces: “I wonder what sort of mechanism it’s got.” Higashino himself notes, “The precinct detective had looked into things that the rest of them had dismissed as insignificant.” Things like where you choose to sit in a taxi or whether you like sweets or who gave the victim a new pair of kitchen scissors. Although his characterisations are not as fleshed out as one would expect from a contemporary murder mystery, Higashino dwells on the ordinary to draw out clues for the morbid. His writing pattern is minimalist, akin to the Japanese painting style of ‘Printmaking.’ And drawing from that, he stays true to the philosophy of the depiction of scenes from everyday life and narrative scenes that are often crowded with figures and ordinary details. And as a result of that the treatment of the story may feel a little bland as sushi at times and not as layered as other contemporary authors such as Jo Nesbo.

Japan is known to be a country which experiences a high suicide-rate and juvenile crime. The extreme emotional pangs can be seen as a reflection of a technologically advanced society with little clinging to the basic kinship of society, especially in urban areas such as Tokyo. Using these highlighters, Higashino analyses the social malaise of his own working-class society and tries to give insights into certain behavioural patterns. Along with Haruki Murakami, Mahoko Yoshimoto and Natsuo Kirino, Keigo Higashino has carved a niche for himself as one of the new waves of post-war Japan authors, who are a formidable group of misfits, outlaws, and introspective urban investigators. And this is a much-required overall enrichment for the literary world.

(The writer is a PhD candidate of development studies at Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines