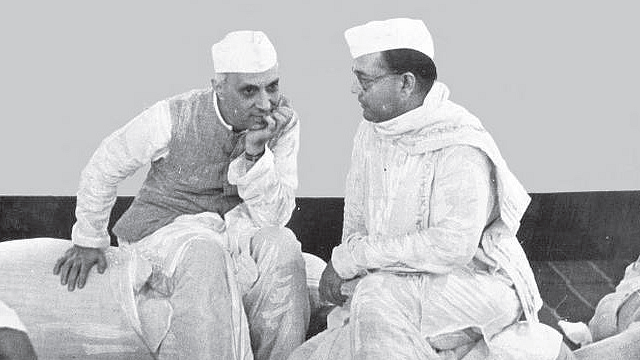

Nehru and Bose: letters reveal they were comrades more than adversaries

Subhas Chandra Bose accompanied an ailing Kamala Nehru from Vienna to Prague. And when his daughter visited Delhi in 1960-61, she stayed at Teen Murti House with Nehru and Indira Gandhi

Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhas Chandra Bose, charismatic stalwarts of the Congress and the Indian struggle for Independence, were comrades, not adversaries.

In June 1935, when the former was imprisoned in India, his wife Kamala needed to go to Europe for treatment of tuberculosis. Bose, who had been exiled to Europe by the British, unsurprisingly took charge by accompanying her from Vienna to Prague where she was to receive initial medical care.

With Kamala’s condition deteriorating, the British permitted Nehru to join her. She was moved to Badenweiler, a Black Forest resort in Germany. Bose messaged Nehru: “If I can be of any service in your present trouble, I hope you will not hesitate to send for me.” Eventually Kamala was shifted to Lausanne in Switzerland, where she prematurely passed away in 1936 in the presence of her husband, daughter Indira and Bose.

Soon after, Nehru left for India to preside over the Lucknow session of the All India Congress Committee (AICC). Bose, still in Europe, wrote to Nehru to underscore: “Among the front-rank leaders of today – you are the only one whom we can look up to for leading the Congress in a progressive direction.”

In January 1938, Bose, a rising star in the freedom movement, visited London for the first time since his graduation from Cambridge University in 1921. While in the British capital, he, not unexpectedly, received a telegram from Mahatma Gandhi informing him of his unanimous election as president of the Indian National Congress for its fifty-first session to be held at Haripura in Gujarat. The message added: “God give you strength to bear the weight of Jawaharlal’s mantle.” Nehru was then the incumbent president.

However, before his anointment, there was the delicate matter of rendering Bande Mataram, a lyrical poem composed in Bengali by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee. The song compared India with the Hindu Goddess Durga and had been incorporated in Chatterjee’s 1882 novel Ananda Math, which was replete with anti-Muslim bias. Yet, it had gained traction in the nationalist movement.

When Nehru asked Bose if the Congress should be identified with what seemed to be an enunciation of Hindu exultation, the latter suggested they should seek Nobel Prize-winning Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore’s opinion. The poet laureate approved of the coinage Bharatmata or Mother India and did not think the first verse of the poem was offensive to any community; but he felt the song as a whole and the literature with which it was associated were liable to upset Muslims. Based on this advice, the Congress distanced itself from Bande Mataram in terms of it equating the nation with a Hindu Goddess and, therefore, one religion.

The internationally reputed American TIME magazine quite exceptionally put Bose on its cover in its edition of March 7, 1938. In his presidential address, he declared: “Our chief national problem relating to the eradication of poverty, illiteracy and disease and to scientific production and distribution can be effectively tackled only on socialistic lines.”

Such a policy, he added, “will require a radical reform of our land-system, including the abolition of landlordism”. He went on to advocate, “a comprehensive scheme of industrial development under state-ownership and state-control will be indispensable”. This was much too left-wing for capitalism-oriented activists in the fold.

As Bose’s term progressed, Gandhians and Congress conservatives increasingly opposed his re-election. Vallabhbhai Patel, an arch rightist, issued a public statement on behalf of his group in the working committee – the highest decision-making body in the party – urging Bose to step aside and allow a unanimous election of their candidate Dr Pattabhi Sitaramayya. As a storm brewed, Tagore, in a letter to Gandhi, urged that Bose be re-nominated. The Mahatma, who was otherwise deferential to the literary luminary, addressing him as Gurudev or ‘respected guru’, replied it would be better for Bose not to run.

Yet, he was stunningly returned. The Mahatma uncharacteristically fumed. “Since I was instrumental in inducing Dr Pattabhi not to withdraw…the defeat is more mine than his…it is plain to me that the delegates do not approve of the principles and policy for which I stand.” In effect, he challenged the Congress to choose between him and Bose.

Nehru felt his younger colleague’s ‘aspersion’ against the old guard of the Congress on the matter of their alleged willingness to compromise with the British was unwarranted. At the 1939 session of the AICC in Tripuri in Madhya Pradesh, Bose was duly re-crowned as president. However, a resolution, which bound him to select a working committee ‘in accordance with the wishes of Gandhiji’, was passed.

This was unacceptable to Bose. At a special meeting of the AICC in Kolkata, Nehru conciliatorily moved a motion calling for Bose to withdraw his resignation. The latter, though, refused.

While attending the fractious AICC meeting in Kolkata, Nehru was a house guest at Subhas’ elder brother and Congress working committee member Sarat’s abode – as he generally was during his visits to the eastern metropolis. The Boses were privately livid at the treatment of a family member treasured as a jewel of the clan. Sarat, however, firmly instructed his children not to express their emotions, emphasising politics should not affect personal relations.

Bose was upset with Nehru for not showing solidarity with him for they had been bedfellows on socio-economic matters. The correspondence between the two that followed reflected undisguised resentment on the part of the former and an apologetic tone in response.

Bose began his copious letter of March 28, 1939 to Nehru by aggressively alleging: “I find that for some time past you have developed tremendous dislike for me. I say this because I find that you take up enthusiastically every possible point against me; what could be said in my favour you ignore. What my political opponents urge against me you concede, while you are almost blind to what could be said against them.”

Nehru disarmingly replied on April 3, 1939: “Your letter is essentially an indictment of my conduct and an investigation into my failings…so far as the failings are concerned, or many of them at any rate, I have little to say. I plead guilty to them, well realising that I have the misfortune to possess them.”

Bose further wrote: “On my side, ever since I came out of internment in 1937, I have been treating you with the utmost regard and consideration, in private life and in public. I have looked upon you as politically an elder brother and leader and have often sought your advice.”

Nehru countered: “I entirely appreciate the truth of your remark that ever since you came out of internment in 1937, you have treated me with the utmost regard and consideration, in private as well as in public life. I am grateful to you for this. Personally I have always had, and still have, regard and affection for you, though sometimes I did not like at all what you did or how you did it. To some extent, I suppose, we are temperamentally different and our approach to life and its problems is not the same.”

The free and frank exchange, though, was not devoid of civility. Before concluding, Bose added: “If I have used harsh language or hurt your feelings at any place, kindly pardon me. You yourself say that there is nothing like frankness and I have tried to be frank – perhaps brutally frank.” Nehru reciprocated: “Frankness hurts often enough, but it is almost always desirable, especially between those who have to work together.” Both, as was their wont, signed off their letters with ‘Yours affectionately’.

Nehru stated before Bose’s Indian National Army’s 1944 campaign to liberate India from Myanmar via the North-East, that he would personally confront the INA and the Japanese forces accompanying it if they entered India. But after Bose’s troops were defeated and the British put officers of the INA on trial at the Red Fort in 1945, he donned a barrister’s gown – having forsaken it decades earlier – to team up with the legendary lawyer Bhulabhai Desai to defend them.

“The INA trial,” Nehru said, “has created a mass upheaval.” In another speech, he asserted: “The trial has taken us many steps forward on our path to freedom. Never before in Indian history has such unified sentiments been manifested by various divergent sections of the population.”

In December 1945, Nehru attended Sarat’s daughter Gita’s wedding in Kolkata. In so doing, he handed over to Sarat Subhas’ burnt and mutilated wrist watch, which his aide-de-camp Colonel Habibur Rehman had requested him to deliver. Rehman was on the ill-fated aircraft that crashed in Taipei on August 18, 1945, causing Bose’s death; but which the former, while suffering injuries, was fortunate enough to survive.

In the winter of 1960-61, Bose’s Vienna-based half-Austrian daughter Anita undertook a maiden visit to India. Predictably, she stayed at Nehru’s official prime ministerial residence of Teen Murti House in Delhi, enjoying his and Indira Gandhi’s personal hospitality.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines