German journalist questions India’s data privacy law: Aadhaar best invention since sliced bread?

In a blog post, German journalist Norbert Haering, rips into the praise heaped on India’s draft data privacy law now before a parliamentary committee. See the link to his blogpost at the end.

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the powerful central bank of central banks, has published a paper that is scandalous in more than one respect. They advocate worldwide adoption of the Indian government’s approach to data-sharing, which will result in every Indian citizen being stripped of all privacy.

The paper, written by four BIS-economists, goes by the name ‘The design of digital financial infrastructure: lessons from India’.

Reading the small print reveals the background. The authors thank the BIS-General Manager, Augustin Carstens, for suggesting the topic.

I read this as: “We did not mean to write this embarrassing piece of propaganda, we were ordered to do so by our boss“.

We also learn that “the substance of the paper arose from a conversation in Nandan Nilekani’s office in Bangalore.”

So, Carstens sent several of his staff over to India to have Nandan Nilekani tell them what to write about Digtial India and the scandal-ridden centralised biometric database Aadhaar and the Indian approach to data sharing. No wonder, the piece is full of the marketing terms that the Indian government uses to sell its pet project.

Augustin Carstens is a former Mexican central banker and high-ranking manager of the International Monetary Fund (IMF). He is a Chicago Boy, one of the many Chicago educated Latin American economists deeply immersed in Chicago‘s market-radical school of thought. He is a member of the secretive Group of 30 (G30), founded by Rockefeller. As many others in that group, he is also an ardent proponent of “financial inclusion“ and measures against the use of cash.

Nandan Nilekani is an Indian IT-billionaire with ties to Bill Gates and, from his early days, a darling and protege of the World Economic Forum. Most importantly, from 2009, he was in charge of the government’s Aadhaar-project, a unique biometric identifier for all citizens and all purposes, into which almost all Indians have been forced by now.

Since Nilekani has been the creator and remains a fierce defender of Aadhaar, it is no wonder that the BIS-paper presents Aadhaar as if it was the greatest thing since the invention of sliced bread, rather than the privacy nightmare that many critics see in it.

The scandals around the scheme are ignored, the criticisms are mentioned very briefly in passing, combined with the grossly inaccurate assertion that critics do not fundamentally challenge Aadhaar, but are only arguing for better privacy laws.

Among the scandals are leaks of Aadhaar-numbers of millions of people and revelations that access to the whole database was sold on the markets for a few dollars. Unlike a password, you cannot change your fingerprints and iris pattern, if your data has been hacked.

Millions of poeple were denied government payouts, because their fingerprints were unreadable due to heavy manual labour, fraud, or malfunctioning biometric reading equipment.

In European countries like Germany, France and Britain, governments have failed in their attempts to erect similar unique identifiers for all purposes, because constitutional courts have ruled them to be in breach of privacy protections of citizens. In the US, people do not even have government-issued ID-cards for these very reasons.

The Indian constitutional court ruled several times that it was unconstitutional to make Aadhaar a requirement to receive government payouts or services. The government simply ignored this.

Aadhaar is one of the pillars of Digital India that the BIS-economists praise. Another one is data sharing with consent which the BIS also praises as an example to be followed. The concept is described in terms of advantages for consumers:

“Empowering individuals through a data-sharing framework that requires their consent: India offers important lessons that are equally relevant for both advanced economies and emerging market and developing economies. Data-sharing rails are designed to prevent data capture by the state or the private sector, instead empowering consumers and businesses to benefit from their own data.”

“In this digital financial infrastructure, consumers – by controlling the access to and management of their own data – can transact in the marketplace without compromising privacy. At the same time, convenient means of sharing data where necessary are incorporated in the infrastructure.”

“This is meant to improve on the current, allegedly problematic situation, where individuals’ counter-parties in economic, social and bureaucratic interactions collect data independently in databases that are not connected and thus incomplete.”

In the words of the BIS:

“In the absence of public initiatives, newly created digital data will tend to be gathered and retained in proprietary silos. The challenge is to create a structure allowing customers to readily access and share their personal data to overcome information asymmetries and lack of trust.”

All this is only for the best of consumers, who are fundamentally untrustworthy and mistrusted and who thus urgently need a chance to shed all privacy. They need a chance to commit to providing the other side in a transaction with complete information about themselves:

“In India, the focus of data policy is to ensure that citizens reap the benefits of the data they generate. Data isolated in silos represent a significant opportunity cost to consumers. Digital data trails can help consumers show evidence of income, businesses attest to revenues and earning potential, thus improving access to credit and other financial services.”

The backbone of the infrastructure to allow everybody to voluntarily submit to this system of complete surveillance are so called account aggregators, which have simultaneous access to all the information that is stored in all participating institutions about all individuals that have an Aadhaar number:

For this purpose, in 2016, the RBI established the legal framework for a class of regulated data fiduciary entities, called account aggregators, which enable customer data to be shared within the regulated financial system with the customer’s knowledge and consent. …

“This will help a credit provider, personal finance adviser or vendor of other financial services that needs data about a potential customer in order to assess the desirability of a transaction, rather than requesting information from the customer on a bilateral basis or through a variety of specialised institutions such as credit bureaus, they will submit the request for information together with the customer’s virtual ID to the account aggregator. Before passing on the request to the financial institutions that hold the requested data, the account aggregator will notify the customer of the entity’s request via the app and ask for consent to share the data.

As centralised databases, notably those under government control, have been considered by a number of constitutional courts as incompatible with the protection of privacy, the route that is taken here is to emulate a central database by a system of interconnected databases, which all work with the same reliable identifier for people, their Aadhaar-number. This is as good as a centralized database, but harder to prohibit for the courts.

The stated goal is, to allow people to obtain credit or an insurance policy with less paperwork. Put differently, the goal is, to enable banks and insurance companies to more easily weed out unattractive customers.

Does this really justify forcing all citizens to accept that everything that is known about them, is collected in a system akin to a central database – a database, to which everybody who is a little more powerful than they are, can obtain access?

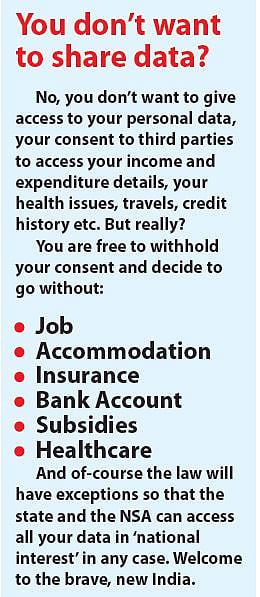

The Indian government (and the BIS) pretend that the condition of consent to data sharing is a strong protection for individual privacy. This is obviously bogus, as anyone knows who has tried to go around the world wide web not accepting any cookies. The choice is regularly to accept or not to get any service or information.

Consent: A Double-edged Sword

The requirement of consent to data sharing is nothing but a Trojan horse to be able do away with privacy altogether.

Once this infrastructure of easy and “voluntary“ sharing of aggregated data is established, everybody who wants any form of credit will have to consent to sharing their data.

The same will be true for anybody wanting to buy any kind of insurance. No insurance company has an incentive forgo asking for this information, if all the others do. If they were more lenient and less nosy, they would get all the bad risks, that others refuse to insure, while the others would insure the good risks.

And, as the BIS-authors do not fail to mention, applications go beyond finance. If you apply for a job, your prospective employers will kindly ask for your permission, to access all information that has been collected and stored about you. All voluntary, of course. You remain free to choose whether you want to be employed and let your employer know everything about you, or retain your privacy and be unemployed.

It does not even end here. Prospective landlords also have a keen and understandable interest in knowing what kind of person is asking to rent their apartment. You will be free to choose, if you want to have privacy and live on the street or give up on privacy and have a place to sleep.

Healthcare is also mentioned

as a field of application. Customers might want to share their complete health records with someone they interact with. Who might that be? Again, insurers and potential employers come to mind.

Would it not be great for consumers to share their complete health history with an insurer or employer, in order to be able to obtain health insurance or a job, which they would not have obtained otherwise? Maybe not. After all, there are all those people, against which insurers and employers would all too happily discriminate against, if they knew everything about them.

It is also envisaged, that customers will get a chance to submit to ongoing intrusive surveillance by providers of (financial) services, as can be read between the lines:

Loan products can be personalised and created in real-time to suit the needs of the customer based on the data provided. After the loan has been disbursed, data-sharing can help monitor the loan on an ongoing basis.

This will be true for the new credit products, which the BIS expects to flourish in this environment: loans that are not secured by assets of the debtor, but by his future income stream, like wages or social benefits.

To obtain such a loan, you might have to submit to letting your creditor monitor your income and expenditure data, and thus your behaviour in general, until the loan is paid back.

If they see that you spent money on something you are not supposed to, while you claim to be unable to repay on time, they can send in the thugs, or the police, to put you in jail.

Of course, the government will not want private entities to be the only ones who can use this nice government-created infrastructure of surveillance. Cutely naive, the BIS-authors say that the government should not look into the data about its citizens that is now so conveniently accessible. They feel obliged, however, to mention, very briefly, that something is already going on in this direction:

“More recently India’s personal data protection bill (Republic of India (2018)) has generated considerable discussion and debate.”.

One provision of the bill is that the central government can exempt any government agency from the bill’s restrictions for reasons of national security, public order or friendly relations with foreign states (read NSA-requests for data). For this reason, the bill in its revised 2019 version was criticized by Justice B. N. Srikrishna, the drafter of the original bill, as turning India into an “Orwellian State”

The bill is currently being reviewed by the Indian Parliament.

With China being very rapidly transformed into a high-tech total-surveillance state and India going down the same route, close to half the world’s population will soon live under such conditions.

(This blog post was written by German business journalist Norbert Haering this week. See his blog at https://norberthaering.de/en/power-control/bis-india-totalitarianism/)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines