Who doesn’t love a cheap hot meal?

Why canteens matter even when 800 million people get free rations through the public distribution system

On my way to Jaipur to pilot test questionnaires for a survey of canteens in select cities, I had dinner on the Vande Bharat train. The next day, I had a meal at an Indira Rasoi canteen. My first thoughts: rotis at the Indira Rasoi were better than those on the [expensive] Vande Bharat.

Canteens such as Indira Rasois (in Rajasthan) and Amma Unavagam (Tamil Nadu) provide freshly cooked meals at subsidised prices (Rs 8 and Rs 5, respectively). They had faded from public memory till a comeback in response to the humanitarian crisis caused by the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns in 2020. For instance, starting with just over 200 in August 2020, Rajasthan had 1,200-odd Indira Rasoi canteens (renamed Shree Annapurna Rasoi) by 2023, with plans to expand the network into rural areas.

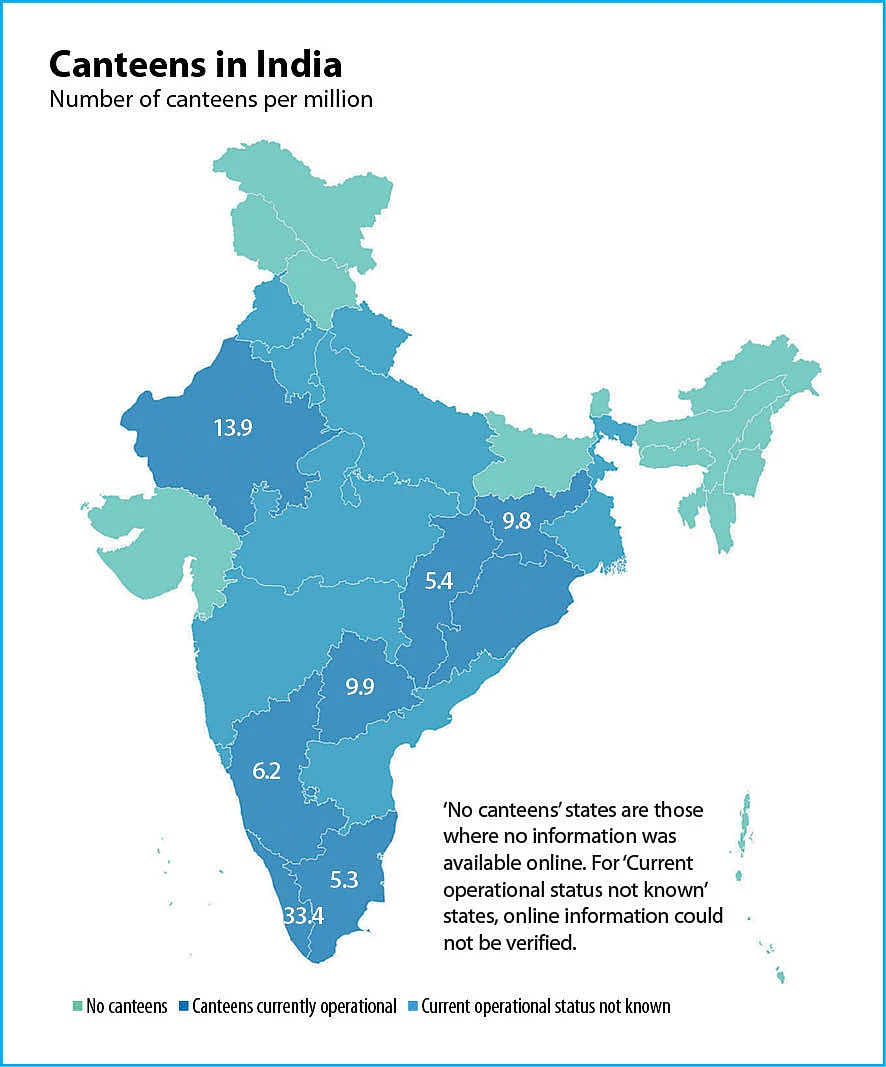

The government-subsidised canteen network is quite widespread in India (see map below), but has somehow not received the kind of policy attention it deserves. Most came up between 2010 and 2020 — Amma Unavagam in 2013, Annapurna canteens (Telangana, 2014), Aahar (Odisha, 2015), Indira canteens (Karnataka, 2017), Indira Rasoi (Rajasthan, 2020), Shiv Bhojan Thali (Maharashtra, 2020).

Few systematic studies exist of these state government-sponsored schemes. For our Canteen Survey 2023, we picked three states — Tamil Nadu, Rajasthan and Karnataka. The survey was undertaken in November–December 2023, with the objective to better understand the potential of such a social policy intervention, how these were actually implemented, and to see if there were any inter-state policy lessons.

It covered 12 cities — Ajmer, Bikaner, Chittorgarh, Churu, Jaipur and Udaipur in Rajasthan; Bengaluru, Bellary and Mysore in Karnataka; and Chennai, Coimbatore and Vellore in Tamil Nadu. In all, we surveyed 704 guests in 174 randomly sampled canteens.

Why canteens when there is PDS?

Some ask why we need canteens to provide subsidised meals when 800 million (80 crore) of our poor get free rations through the public distribution system (PDS). Why not expand PDS coverage instead, they say, rather than have “yet another scheme” for food security. Another response is to focus instead on ‘portability’ in the PDS via ‘one nation, one ration card’.

While PDS rations do boost food security for those who have cooking facilities, this is not always the case in urban areas, especially among migrant workers. Between 11 and 47 per cent of our respondents had no cooking facilities at home. For them, even a portable PDS, which provides dry rations, would not guarantee food security.

In popular discussions, canteens are characterised as a food security measure for the destitute, homeless, vagrants or beggars. True, these people benefit hugely from canteens, and they made up nearly a tenth of survey respondents. Nearly a fifth (17 per cent) reported sleeping hungry sometimes before canteens opened in their areas.

Besides those for whom hunger and destitution are a chronic problem, there are people like 46-year-old Haroon in Churu — when he was laid up with a fractured foot, he had to sleep hungry a few times till he chanced upon a canteen.

It is wrong, though, to view canteens through a lens of chronic or transient vulnerability alone. They are extremely attractive to working people as well because they are cheap and offer nutritious food. The subsidy provided by canteens is substantial — in Rajasthan, at the time of the survey, customers were paying Rs 8 for a thali that costs Rs 25.

Canteens remedy several market failures. First, when food inflation is high, they provide an assured supply of food at fixed prices. Second, street food tends to be unregulated and not necessarily prepared in hygienic conditions. By setting some standards, canteens can ensure availability of safe hygienic food, with possible spillover effects on private street-food vendors. Third, if state governments pay greater attention to nutrition in canteens, it can also raise the bar for meals available from street vendors.

The limited availability of nutritious food is not merely because of the cost involved but also poor nutrition education. A hidden benefit of canteens is the creation of democratic spaces, which has special significance in India, where caste, class, gender and religion still influence social interactions.

There are few public places in India where slum dwellers, the homeless, or those living in shelters, bus stands and so on (12–28 per cent of survey respondents) share space with those who live in the non-slum areas of cities (nearly 50 per cent of respondents).

Many respondents commended the inclusive nature of canteens. “From government servants to daily wage workers, all eat here together,” said one in Bellary. “Everyone comes — those who have money and those who don’t”.

The mixed background of canteen staff and guests is also noteworthy. Dalits (often excluded, especially when it comes to food), Adivasis and Muslims comprised 16 per cent of guests in Karnataka, 25 per cent in Tamil Nadu and 33 per cent in Rajasthan.

The canteen staff too is from mixed social groups. In Rajasthan, only a tenth of canteens in the survey were lacking this diversity in their staff mix, though in Tamil Nadu, that proportion was higher (nearly 30 per cent). The staff are employed as cooks, as helpers, as cashiers at billing desks, suggesting there is no social segregation in the roles assigned to them.

For women, canteens also create employment opportunities. Women were well represented among canteen staff (only 8 per cent of canteens surveyed had no female staff). In Tamil Nadu, all the staff were women. In Rajasthan and Karnataka, the teams were mixed, though Rajasthan had more women employees than Karnataka.

Who eats at canteens

On the day before the survey, canteen staff reported an average of 247 guests, with little variation across states; the lowest was 224 in Tamil Nadu. Canteens have regulars (more than half reported eating at the canteen every day or almost every day), sporadic and first-time guests (those accompanying patients to hospitals, visitors to the city for administrative or legal work, travellers from train stations and bus-stands etc.)

The regulars fall under five broad categories — working men, women, students, the elderly and people in assorted difficult situations. Working men were the largest group among our respondents. Some were migrants to cities from within the state and some from faraway places. One Swiggy delivery worker in Bengaluru (originally from Assam) said when he needs to eat, he “looks for a nearby Indira canteen on Google Maps”.

Locals whose jobs require them to be on the move (autorickshaw drivers and gig workers) find canteens very convenient. There are others who live in accommodation without cooking facilities or have little time to cook.

Women were a minority among guests (9-13 per cent of respondents), but canteens give them relief in more ways than are obvious. Since women cook at home for families, it saves them productive time when family members eat in a canteen; for women who combine house work with paid work outside, canteens are a lifeline.

In most cities we surveyed, there were some canteens near colleges or universities. More than a tenth of their guests were students. For students in hostels or in paying guest accommodation, the canteens are a godsend. Affordable food that tastes like “ghar ka khana” (home-cooked food) was a common refrain.

The elderly (age 60 and above) made up nearly 20 per cent of guests in Tamil Nadu, but fewer in Karnataka (6 per cent) and Rajasthan (8 per cent). For them, canteens mean a simple, easy-to-digest meal at an affordable price, besides being a safe social space with a sense of community.

There are also people in sundry difficult situations — we met guests who admitted to mental health issues, or strained relationships with spouses and family. Their numbers may not be large but for them too, canteens are a source of healthy food they can avail of with dignity.

Canteens can do better

The most important area of necessary improvement is the menu, especially the provision of nutritious food such as eggs, yoghurt, buttermilk, fresh vegetables and a variety of grains. At the very least, some items can be provided as ‘top-ups’ at cost price.

In Rajasthan, cultural factors, including a high proportion of vegetarians in the population, means canteen meals are vegetarian — roti, dal or kadhi and one sabzi. At some canteens, we saw guests bring their own buttermilk or yoghurt.

Karnataka turned to centralised kitchens for its canteens. Contractors (religious or otherwise) are best avoided for such government programmes because they try to minimise expenses. When large suppliers have religious convictions (as a supplier of school meals in Karnataka did), they can prevail on state governments to keep eggs, an easy source of nutrition, off the menu.

In Tamil Nadu, there is neither resistance to animal proteins nor any of the problems arising from centralised kitchens. The present neglect of canteens in the state could be for political reasons. The state government is in a bind — it does not want to shut down a popular scheme but nor does it want to put more money into a scheme so closely associated with a political rival.

The staff tended to blame the present government for playing politics, though the neglect possibly set in earlier. After all, no change in the menu or increase in wages occurred between 2013 and 2021, when the party to which the workers owed their jobs was in power.

Canteens need — and deserve — more guaranteed funds, so they become a regular feature of the social protection framework in India. Before his government fell in late 2023, Ashok Gehlot had allocated Rs 700 crore for Rajasthan’s Indira Rasoi Yojana; that budget has been halved. By showing some political magnanimity, governments have the opportunity to seize ownership of a very useful scheme.

Reetika Khera is a development economist and teaches at IIT Delhi. A longer, annotated version of this essay first appeared in The India Forum

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

Published: 21 Jul 2024, 3:40 PM