A life that ties them up in knots

Their carpets may adorn the walls of Parliament House, but life for Mirzapur’s weavers is an unrelenting grind

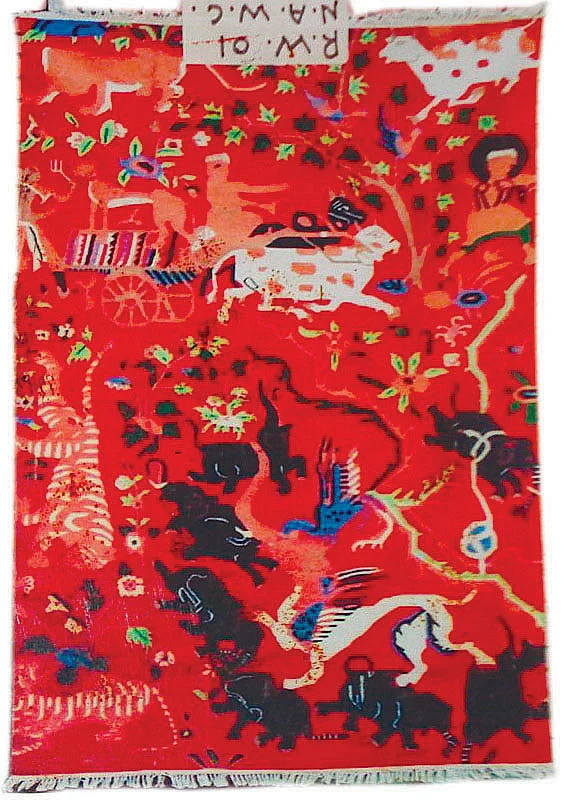

Speaking to PARI as he rests, Toofani Toofani and his team of weavers have been working since 6.30 am. At the pace of 12 inches a day, the four of them will take 40 days to finish the 23x6 feet galicha (carpet) they are working on.

At half past noon, Toofani Bind finally sits down to rest on a wooden bench. Behind him, in the tin shed where he works, white cotton threads hang from a wooden frame at his workshop in Purjagir Mujehara village of Uttar Pradesh.

This is the heart of the state’s carpet weaving industry, introduced in Mirzapur by the Mughals, and industrialised by the British. Uttar Pradesh dominates the national production of rugs, mats and carpets, accounting for half the national output (47 per cent), says the 2020 All India Handloom Census.

The road leading up to Purjagir Mujehara village gets narrower as one gets off the highway from Mirzapur city. On either side are pucca, mostly one-storeyed houses, as well as kachcha homes with thatched roofs; the smoke from cow-dung cakes rising in the air. In the day, men are hardly visible outdoors, but women can be seen doing household chores like washing clothes under the hand pump or talking to a local vendor of vegetables or fashion accessories.

There are no signs that this is a weavers' locality — no carpets, or galicha as the locals refer to it, hang or are stacked outside. Although households have an additional space or room allocated for carpet weaving, once ready, middlemen pick it up for washing and cleaning.

Speaking to PARI as he rests, Toofani says, “I learned it (knotted weaving) from my father and have been doing this since I was 12–13 years old.” His family belongs to the Bind community, listed in the state as an Other Backward Class (OBC). Most weavers are listed under OBC in UP, says the census.

Their home workshops are cramped spaces with mud flooring; a single window and door left open for ventilation, the loom taking up much of the space. Some workshops, like Toofani’s, are long and narrow to accommodate the iron loom where multiple weavers can work at the same time. Others are within the house and use a smaller-sized loom mounted on an iron or wooden rod; the entire family lends a hand with the weaving.

Toofani has been placing stitches with woollen threads on a cotton frame — a technique known as knotted (or tapka) weaving, tapka being a reference to the number of stitches per square inch of the carpet. The work is more physically demanding than other forms of weaving for the artisan must manually add the stitches.

To do this, Toofani has to get up every few minutes to adjust the frame of sut (cotton yarn) using a dambh (bamboo lever). The continuous squatting and rising takes a toll.

Unlike knotted weaving, tufted weaving of carpets is a relatively newer form that uses a handheld machine for embroidery. Knotted weaving is harder and the wages are lower, so many weavers have switched from knotted to tufted in the past couple of decades. Many have quit altogether, the earnings of Rs 200-350 a day simply not enough. In May 2024, the state’s labour department announced daily wages for semi-skilled labour at Rs 451, but the weavers here say they are not being paid that amount.

There is competition too, for the Purjagir weavers, says Ashok Kumar, deputy commissioner of Mirzapur’s industries department. In UP, carpets are also woven in the districts of Sitapur and Bhadohi. “There is a slump in demand that has affected supply,” he adds.

There were other problems as well. In the early 2000s, allegations of child labour in the carpet industry soured its image. The arrival of the Euro made Turkey’s machine-made carpets better priced, and slowly the European market was lost, says Siddh Nath Singh, a Mirzapur-based exporter. He adds that the earlier state subsidy of 10-20 per cent has dropped to 3-5 per cent.

“Instead of earning Rs 350 a day for a 10-12 hour shift, why not work in a city for Rs 550 as daily wages,” points out Singh, who is a former chairman of the Carpet Export Promotion Council (CEPC).

Toofani once mastered the art of weaving with as many as 5-10 coloured threads at one go. But the low wages have dampened his enthusiasm. “They (middlemen) are the ones who commission work. While we keep on weaving day and night, they earn more than us,” he says dejectedly.

Today he earns Rs 350 for a 10-12 hour shift, based on how much he has been able to weave; his wages are paid at the end of the month. But he says this system needs to go, for it does not take into account the hours he has put in. A lumpsum payment of Rs 700 a day should be paid as labour charges for this skilled work, he feels.

The middleman who gets them the contracts are paid by the gaj (one gaj is about 36 inches). For four to five gaj, which is the length of an average carpet, the contractor will earn around Rs 2,200 while the weaver will only earn around Rs 1,200. The contractors, however, pay for the raw material — the kaati (woollen thread) and sut (cotton yarn).

Toofani has four sons and a daughter who are still in school. He does not want his children to follow in his footsteps. “Why should they also do the same thing that their father and grandfather have spent their lives doing? Shouldn’t they study and do something better?”

In a year, Toofani and his team weave 10-12 carpets, working 12 hours a day. Rajendra Maurya and Lalji Bind, who work with him, are both in their 50s. “The first step in making a galicha is the taana,” Toofani says. “It involves mounting the frame of cotton thread onto the loom.”

In a rectangular room measuring 25x11 feet, there are trenches on either side where the loom is placed. The loom is made of iron with ropes attached on one side to hold up the frame of the carpet. Toofani bought it on loan five or six years ago, paying back Rs 70,000 in monthly instalments. “In my father’s time, they used wooden looms placed on stone pillars,” he says.

Weaving takes a toll on the artisan’s health. “It has affected my eyesight over the years,” says Lalji Bind, who has been in this profession for 35 years. He has to wear glasses while he works. Other weavers complain of back ache and even sciatica. They feel like they had no other choice but to take up this profession. “Our options were limited,” Toofani says.

In rural UP, almost 75 per cent of weavers are Muslim, says the census. “There were around 800 families 15 years ago that were into knotted weaving,” recalls Arvind Kumar Bind, a weaver from Purjagir, “today that number has come down to 100.” That’s more than a third of Purjagir Mujehara’s population of 1,107 (Census 2011).

In another workshop nearby, Baalji Bind and his wife Tara Devi are working silently on a soumak, a knotted carpet. The only sound is the occasional snip of threads with a knife. A soumak is a single-coloured galicha with a uniform design, and weavers who have smaller looms prefer making it. “I will get 8,000 rupees for this piece if I finish within a month,” says Baalji.

In Purjagir and Bagh Kunjalgeer, both weaving clusters, women like Baalji’s wife Tara work alongside and account for almost a third of all weavers. But their labour is not acknowledged by others around them. Even children pitch in when they can, their labour helping things speed up.

Hajaari Bind and his wife Shyam Dulari are working to finish a carpet in time. He misses his two sons who used to help but have now migrated to Surat for wage work. “Bachchon ne humse bola ki hum log isme nahi phasenge, papa (my children told me they didn’t want to be trapped in this).”

The falling incomes and hard labour are pushing not just the young away, but even 39-year-old Shah-e-Alam, who left weaving three years ago and now drives an e-rickshaw. A resident of Natwa, 8 km from Purjagir, he had started weaving carpets when he was 15, and over the next 12 years, moved from knotted weaving to becoming a middleman in tufted weaving. Three years ago, he sold off his loom.

The state government’s ‘One District, One Product’ scheme provides financial aid to carpet-weavers while the Centre’s Mudra Yojana offers loans at concessional rates. But weavers like Shah-e-Alam are not aware of these schemes.

A short drive from Purjagir Mujehara, in the neighbourhood of Bagh Kunjal Geer, Zahiruddin is engaged in the craft of gultarash, finetuning the designs on a tufted carpet. The 80-year-old had enrolled for the Mukhyamantri Hastshilp Pension Yojana. The state government scheme, started in 2018, ensures a pension of Rs 500 to artisans over the age of 60. But after receiving the money for three months, Zahiruddin says, the pension stopped abruptly.

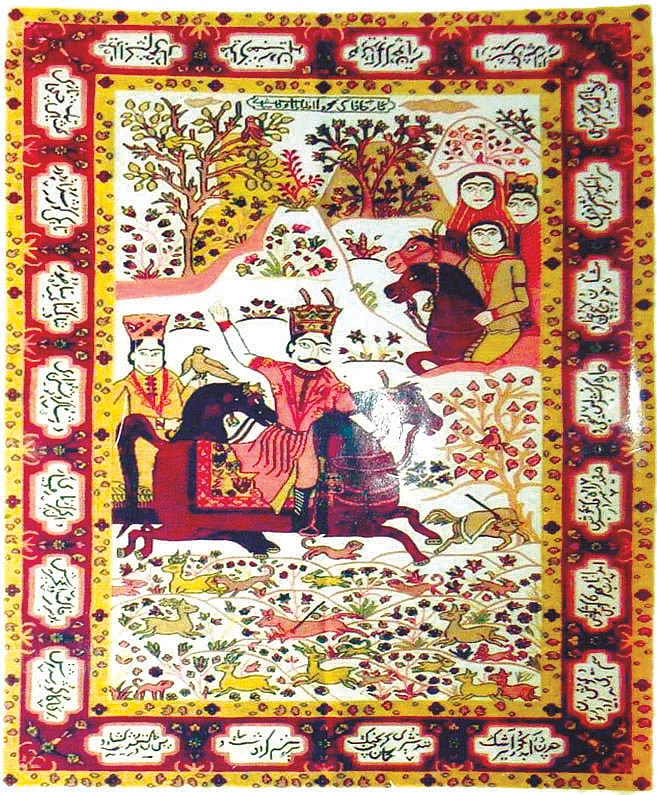

In the same neighbourhood as Zahiruddin, Khalil Ahmed lives with his family. In 2024, the 75-year-old received the Padma Shri for his contribution to durries. Browsing through his designs, he points to an inscription in Urdu: “Is par jo baithega, woh kismat wala hoga (the one who sits on this carpet will be a fortunate one),” he reads out.

But good fortune eludes those who weave them.

All photographs courtesy author on behalf of PARI

The article first appeared courtesy People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines