The versatile vocalist, Krishnarao Shankar Pandit

July 26 marked the 125th birth anniversary of the legendary Hindustani Classical musician

I have had the great fortune to be born in the family of the legendary figures. Not only that, I also had the honour to learn from one of the giants of North Indian classical music, Krishnarao Shankar Pandit, my azoba (grandfather).

Born on July 26, 1893, in Gwalior, Krishnarao Shankar Pandit was the son of Pt Shankar Pandit. He is worshipped like a celestial figure in the field of music. His rigorous talim began at the age of three. His father, Shankar Panditji would take Krishnaraoji at 4 am to Amkho, a valley surrounded by mountains to teach him the swara sadhana, as then the sound would reverberate in echoes.

From the kharaj (base notes) to the taar saptak (higher octaves), notes were practiced. It’s no wonder that throughout his life, he had the gift of being able to traverse all the three octaves with ease.

Besides the vocal training, he was also taught instruments such as the pakhawaj, tabla, been and sitar. For riyaz he would practise playing the tanpura with the right hand and dagga with the left. This would result in an impeccable riyaz of swara, raga and rhythm all together. He practised between 14 to 15 hours a day. Such was his concentration that even the food would be served where he practised. To sum up, just as a high- storeyed building needs a deep and firm foundation to be laid, similarly to be a versatile musician a strong foundation has to be laid under the able guidance and direction of a guru.

Before the advent of microphones, Krishnaraoji performed at the Tansen and Harivallabh Festivals, where an audience of upto 20,000 thronged to hear him. His voice had that kind of stamina and resonance. It seems unimaginable now. The vocalists today insist on microphones even for a small gathering!

He described his participation in what has been described as the oldest festival of Indian Classical Music, Harivallabh Sabha in Jalandhar like this. ‘When I performed here, the audience comprised of local, farmers, labourers and villagers. They would laugh at the music initially, but later this audience itself became my fans.’ That’s how he cultivated the art of listening amongst the masses.

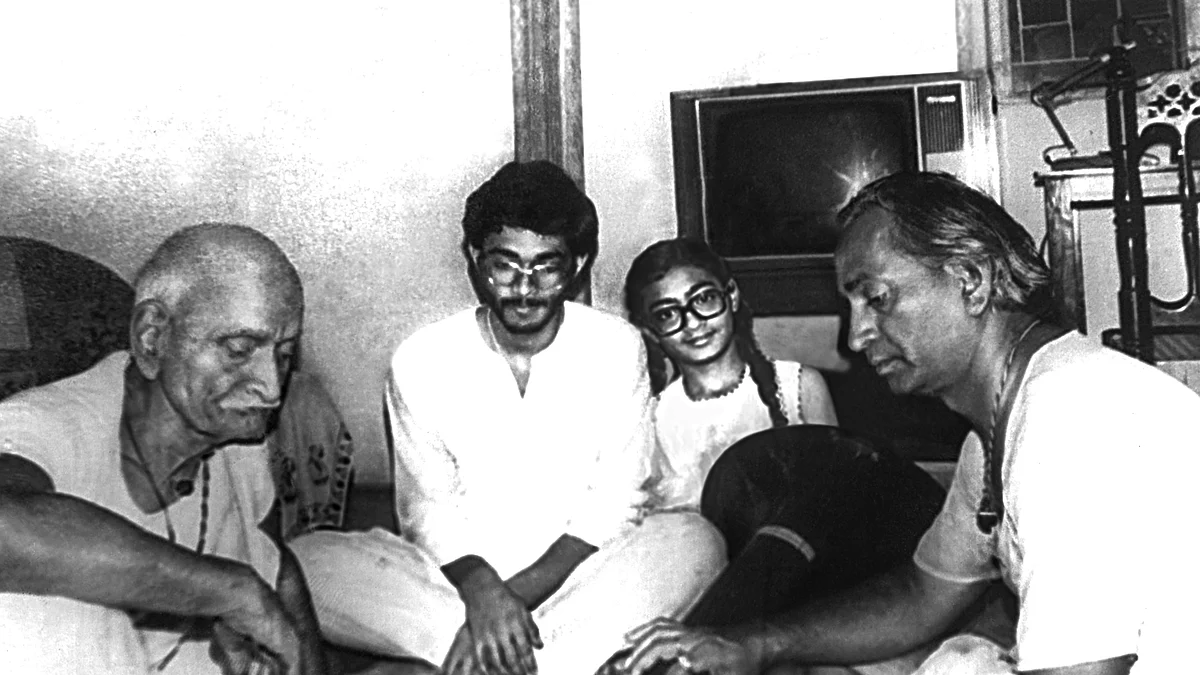

Another reason for this exceptional stamina was that besides rigorous training in music, exercises were taught to keep the body healthy, which included yoga, pranayam, swimming, wrestling and malkhamb. He continued exercising till the end. Krishnarao sang till the ripe age of 86! The recordings that are available were all done in his old age. One can only imagine what his gayaki would have been in his youth. I was very fortunate to spend time with him and receive talim from him. The very fact that I was born in the family is a privilege. My brothers, Tushar and Atul, and I would regularly be taken to Gwalior to for lessons.

Music was a way of life for him. Not only was it about the talim, but azoba (as I fondly called him in Marathi), would share his childhood memories, interesting anecdotes, his talim, sadhna, about the legends of Gwalior, status of music that time, mehfils, and fine aspects about presentation.

One such story was about Raja Man Singh Tomar (1486-1516) founder of the Gwalior school of Music and father of the Dhrupad style. His queen Mrignayani and him were accomplished musicologists. There is a very interesting tale as to how Raja Man met Mrignayani. Once while hunting near Rai Village, the Raja saw a beautiful Gujjar girl separating two fighting bullocks by her bare hands. The Raja was so much taken aback by the sheer strength and beauty of the Gujjar girl that he proposed for her hand in marriage. The Gujjar girl put forward terms for marriage. First that a separate palace be constructed for her, second that water from her village Rai, be made available to the palace. He agreed to both the terms and the Gujari Mahal was constructed just near the Gwalior gate.

Before the advent of microphones, Krishnaraoji performed at the Tansen and Harivallabh Festivals, where an audience of upto 20,000 thronged to hear him. His voice had that kind of stamina and resonance. It seems unimaginable now. The vocalists today insist on microphones even for a small gathering!

Another incident etched in my memory is the historical incident of Ustad Nissar Hussain Khan living in our house from 1886 till his death in 1916. This happened after the Regency Council took over and neglected the court musicians and reduced their salary. Nissar Hussain Khan resigned from the court and came to live with his favourite disciple Shankar Rao Pandit (my great grandfather). Khan sahebs coming to our house and staying like a family member was a very rare incidence in those days because of two reasons.

Firstly, because learning music was a difficult and arduous task as musicians who enjoyed royal patronage wanted nothing for their upkeep, especially when they were used to leading ascetic life. They taught if they were so pleased. One could not become their disciple just by offering some amount. Secondly, it was almost impossible in those days to conceive of a Muslim ustad, living in the home of Brahmin disciple, considering the social structure. Not only that, Khan saheb called himself Nisar Bhatt, wore the sacred thread and practiced vegetarianism. It was a unheard of for an Ustad to live in the house of his pupil and then also teach.

Another interesting incident narrated by him was how Ustad Nissar Hussain Khan got free passes for railway travel throughout India.

Ustad Nissar Hussain Khan was very fond of travelling. Once while in Calcutta, he went to the Governor General’s residence where a show of gymnastics on the rope was being watched by him. After the show was over, Khan saheb saluted him. The governor general was impressed by this 6-feet tall and majestic personality that he was asked to introduce himself. When Khan saheb revealed that he was a vocalist, the governor General asked him to sing and Khan saheb sang the then national anthem – “God save the King”. Pleased, he asked him to sing more. Then, Khan saheb then sang a self-composed composition based on names of different railway stations with the tempo of a train.

Impressed, the Governor General asked what Khan saheb wanted, assuming he would ask for money. But he said that he wanted the passes to travel in the train for himself and two of his disciples. It was granted.

Azoba was concerned about the tradition going forward. Till his death in 1989, he continuously kept track of our progress in music. When he found out that Tushar (my eldest brother) had enrolled in a B.Com. (Hons.) in Delhi University, he was upset and called our father to convince Tushar to pursue music Subsequently Tushar had to withdraw from college.

As a guru he was very strict. During our talim with him the first thing that was taught was voice culture. While learning a raga, a number of compositions are taught so that we understood the depth of a raga. We were fortunate that our debut performance at the Pt. Krishnarao Shankar Pandit Prasang organized by Bharat Bhawan in Bhopal happened while he was alive. Azoba was not only happy to hear us sing, but seemed contended too.

Krishnarao Shankar Pandit was ahead of his times. One of his foremost contributions to Hindustani music was the establishment of a school of music in 1914. He is one of the pioneers in the field of the notation system in Hindustani classical music and has written about it in the ‘Memorable incidents of life’. The need for the notation system was felt by him for better manifestation amongst students. He formed the notation system early in life. Krishnaraoji started working towards it from 1910-11 and by the time the school was established in 1914, the outlay of the notation system was ready. The Alijah Durbar Press of the Gwalior state agreed to print it. The moulds of the notation signs were specially prepared for the purpose and finally in 1924 two books were published. Krishnaraoji made concrete attempts to preserve music for later generations. At a time, when many musicians opted to not share their knowledge or even allow their riyaz to be heard, Krishnaraoji opened the doors of knowledge to all disciples. After All India Radio came into being, many artists refused to record, but he whole-heartedly supported All India Radio in broadcasting their music from all the stations of undivided India.

Some of the salient features of Krishnaraoji singing were: a full-throated, pure and majestic aakar to transverse over three octaves effortlessly, artistry in rendering of compositions or bandish bharna, purity of the raga, a rich treasure of different types of compositions, delineation of the raga according to the composition with ashtang gayaki (eight-fold style), dominant use of behalava, meend, gamak and their different varieties, an extraordinary control over his voice, an exceptional taiyyari, and an extraordinary control over rhythm.

Krishnaraoji was awarded all generously, but he continued to believe that his best award was the love and respect that people had for him.

Of such great people, the Bhagvad Gita says: Oh Arjun, he who controls his senses and follows the karmayoga with a sense of detachment is a supreme being.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

- Gwalior Gharana

- Krishnarao Shankar Pandit

- North Indian Classical Music

- Pt Shankar Pandit

- rigorous talim

- swara sadhana

- Tansen festival

- Harivallabh Festival

- Gwalior school of Music

- Raja Man Singh Tomar

- Dhrupad style

- Ustad Nissar Hussain Khan

- Nisar Bhatt

- Pt. Krishnarao Shankar Pandit Prasang

- Alijah Durbar Press

- Great Masters

- Master of Music

- gayaki