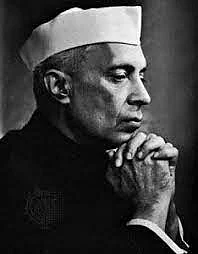

Nehru’s Word: The US visit was an event of some historic significance

"My speeches generally evoked some kind of an emotional response which surprised me. More particularly, my speech at Columbia University had a marked reaction on intellectual America"

Jawaharlal Nehru’s first state visit to the US as the prime minister of India came in October 1949 and lasted almost a month. President Truman sent his own plane to bring Nehru from London. Nehru addressed both houses of the US Congress separately on 13 October.

He also spoke at four major universities—Columbia, San Francisco, Chicago and Wisconsin, and held four major interactions with the press at Washington, New York, the UN, and San Francisco, apart from being honoured with receptions and banquets by civic bodies and associations. He also had private meetings with many distinguished persons, the most well -known being with Albert Einstein. The prime minister held a press conference immediately on arrival in Bombay. In a letter the chief ministers, Nehru gives an account of his visit.

---

A great deal has been written about my visit to America. Every word that I uttered there in public has been reported. Since my return also I have said something about this visit.

There is little that I can add to it. I have little doubt that looking at it objectively and impersonally, it was an event of some historic significance. Certainly, the people in America looked upon it as such and, from all accounts, people in other countries also attached great importance to this visit.

Whatever the personal factor might have been, this visit certainly became in the eyes of many an event in the development of a new historic process. It represents the ending of the period of Asia’s subservience, in world affairs, as well as in domestic matters, to Europe and America. It was a recognition, in a sense an awareness of this major fact of our age.

India, of course, counted in this picture. But it was something even more than India that I spoke about and that people felt. This does not mean that India or Asia have suddenly pushed themselves to the front and made their weight felt by virtue of any strength that they might possess, military or economic.

They have no such strength today, except potentially and rather negatively. Nevertheless, the fact that something vital, historic and of far-reaching consequence was happening in Asia came before the people of the West and compelled them to refashion their world view.

I was greatly affected by the warmth of the welcome that I received, both in the United States and in Canada. That welcome was not merely an official welcome, but had a strong popular element in it. It grew in volume and quality during the later part of my stay. This in itself indicated that what I was saying there was touching some chords in the minds and hearts of the people. Perhaps, this is the most significant part of it all.

My speeches generally, addressed to a variety of audiences, evoked some kind of an emotional response which surprised me. More particularly, my speech at Columbia University had a marked reaction on intellectual America and I received many letters about it from persons important in the world of politics, literature and science. (Speaking at the Columbia University on 17 October, Nehru explained India’s policy of ‘detachment’ from power blocs in the interest of world peace and emphasised that “there was some lesson in India’s peaceful revolution which might be applied to the larger problems of the world today”. He appealed to all thinking men and women in the world to recognise the great potential contained in Mahatma Gandhi’s moral weapon for achieving world peace.)

It seemed to me that there was a state of mental unrest and disillusion in the minds of those who think. There was a sense of dissatisfaction at the general trend of world affairs and, at the same time, a sense of helplessness and doubt as to what should be done. What I said, simple enough as it was, appeared to supply some kind of vague answer to this questioning.

That answer was vague enough and indeed I myself have no clear answer in my mind. Nevertheless, because my approach was somewhat different and because I spoke to them with all frankness and sincerity of purpose, I struck a responsive chord in their minds, and for the moment greatness was thrust upon me.

All this led me to think that in spite of the conflicts and hatreds and passions that consume our unhappy world, there was a widespread desire for peace and cooperation among nations and a search for some way to achieve it.

I approached the American people in all friendliness. I was not prepared to be swept away by any passing wind. But I was receptive in mind and frank in approach. As always happens in such cases, the reaction was friendly and frank, even where there was a difference of opinion. That again led me to think how wrong it is for us, as individuals or as nations, always to criticise the other and to point out defects in others…

If this psychological approach was adopted by us in our lives and in our policies, most of our problems would be easy of solution. That, I take it, was the basic approach of Gandhiji, and that was why he drew out the best in us, weak as we were. Even his opponents bowed down before that greatness of spirit and deep understanding of human nature.

I was interested in getting such help as was possible in the economic and technical sphere from the United States. I mentioned this, though rather casually. I realised that what was of more fundamental importance was the general reaction of the American people towards India and towards Asia. If that was friendly and cooperative, other things would follow. So, I concentrated on producing that friendly reaction….

Thus, there was no deal in so far as I was concerned, either political or economic. I left business talks to others like our ambassador and shri Chintamani Deshmukh. I supplied them with an atmosphere which was very favourable for any talk or approach.

(Selected and edited by Mridula Mukherjee, former Professor of History at JNU and former Director of Nehru Memorial Museum and Library)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines