NRC: Making sense of the ticking time bomb

Politics, prejudice, hazy guidelines and poor training have vitiated the process of updating the NRC in Assam. It threatens to snowball into a humanitarian crisis and an international scandal

Zubirun Nessa sits by the window at her home in Mongaldoi and watches the dark clouds gather over the Brahmaputra. The chants of Axomiya poetry in her neighbourhood and the impending flood has left her uneasy.

She was declared a foreigner as a Member of the Foreigners Tribunal found a discrepancy in her age mentioned in the voters’ list and in other documents. While such discrepancies are not uncommon and are due almost always due to clerical errors in government departments, the minor discrepancy was enough to make up the Member’s mind.

He also found the fact that Zubirun was married to her cousin alien to Assam. And although her father has been accepted as an Indian citizen, she is officially a foreigner. Especially insensitive and despicable was the closing remark of the member of the Tribunal who flippantly wrote on the order, “The OP has clearly ‘gifted’ seven children to India. It is time now to send her off requiring me to answer the reference accordingly.” She is not alone.

Assam is the melting pot of two great civilisations – India and China, creating its own inimitable history and culture. At the beginning of the 13th century, Sukaphaa established the Ahom Kingdom. Sukaphaa, had migrated from Mong-Mao, an area now in China to the present day Nagaland. The Ahom kingdom was home to both Hindus and Muslims, to both Shankar Deb and Azaan Fakir.

For six centuries, the Ahoms held on to their kingdom till they were defeated by the Burmese. This was followed by the First Anglo-Burmese War and the signing of the Treaty of Yanbado in 1826.

The British acquired not just the area around the Brahmputra – Assam, Manipur along with an almost complete hold over Cachar Kingdom and Jaintia Hills. They also acquired the Arakan (Rakhine) region which today is at the epicentre of the Rohingya conflict.

It was only in 1912 that Assam was created by the partition of Bengal. Its capital was in Shillong. When independence came, the Sylhet referendum decided in favour of joining.

Pakistan, but Barak Valley chose to remain a part of India.

Assam’s most prominent leader Gopinanth Bordoloi played an important role in convincing a number of Muslim majority districts on the basis of linguistic and cultural ties to remain in India and thus effectively saving India’s chicken neck or the Akhnoor Dagger. It is this area which to this day is the reason behind China’s Sikkim aggression plan and its attempt to isolate the area from the rest of India.

However, in early 60s, there was a movement in Assam over language. Assamese speakers were less than 50 per cent in the state which meant Assamese couldn’t automatically become the official language of the state. The reason for this was the presence of Bengali-speaking people. But a sacrifice was made – Bengali Muslims of Western Assam would declare their mother tongue as Assamese which would make Assamese as the majority language in the state which became the medium of education for next generations to come.

Though they would speak Bengali at home, they would read or write in Assamese, creating a dual identity but even after passage of fifty years and having in fact preserved the Assamese language and culture, they are now ironically deemed to be outsiders or ‘Bohiragoto’.

Peace was short-lived and trouble began when West Pakistan began dominating East Pakistan, leading to the entry of refugees into India. On March 19, 1972, an agreement was signed between Prime Ministers Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Indira Gandhi, determining various issues between the two countries including choosing 1971 as the cut-off year to identify Bangladeshi refugees.

This was the same year when reorganisation also happened in other states of the North East, under the North-Eastern Areas (Reorganization) Act, 1971 which led to the formation of Manipur, Tripura, Meghalaya and the Union Territories of Arunachal Pradesh and Mizoram. Assam, that we know of today, emerged only at this time.

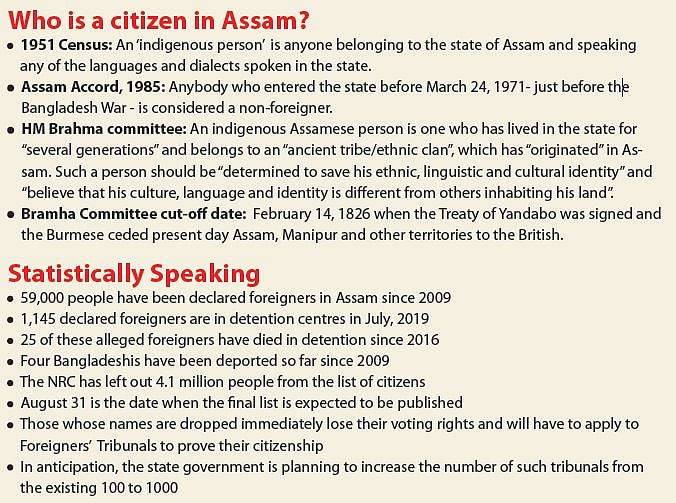

What followed was a unity based on the Bengali identity and the area transformed into a stronghold of Congress backed by the Ali, Coolie and Bangali (the Muslims, the tea planters and the Bengalis). This triggered issues of Assamese ethnicity and identity issues began to simmer, leading to a state-wide student movement called the Assam Agitation. The agitation focussed on illegal immigration fuelled by the fear that the Assamese might become a minority in their state. This led to the Nellie massacre and the signing of the Assam Accord in 1985 between the Government of India, Government of Assam and leaders of the Assam agitation.

As per the Accord, those Bangladeshis who entered between 1966 and 1971 would be barred from voting for 10 years. It declared that the international borders would be sealed and all persons who crossed over from Bangladesh after 1971 were to be deported. Though the accord brought an end to the agitation, some of the key clauses are yet to be implemented. It has kept some of the issues festering.

The National Register of Citizens (NRC) is a register prepared after the conduct of the Census of 1951 in each village, showing the houses or holdings in a sequential order and indicating against each house or holding the number and names of persons staying there. The NRC has been published only once in 1951. Many today don’t realise that the present exercise is merely an updating of the NRC and is not a proof of citizenship.

In December 2014, a division bench of the Supreme Court ordered that the NRC be updated in a time-bound manner. This NRC of 1951 along with the Electoral Roll of 1971 (up to the midnight of 24 March 1971) are together called Legacy Data. Persons and their descendants whose names appeared in these documents find their name in draft NRC.

The NRC was expected to put an end to speculations about illegal immigrations and deter entry of future migrants illegally into India. It also provided respite to those who had until now been suspected of being Bangladeshi and finally avail benefits available to Indians.

Sofia Khatun was one of them. An elderly woman, who spent close to three years in Kokrajhar detention camp, she was granted bail by the Supreme Court when six of her brothers filed affidavits stating that she is in fact their sister and they have never been suspected to be a foreigner. All the six brothers also showed their readiness to undergo DNA test in order to prove their claim.

Ashraf Ali and Kismat Ali, hailing from Bihar and Uttar Pradesh respectively, spent close to three years in detention centres due to an ex parte order declaring them to be foreigners.

Not everyone was as lucky. Many found their names on the first list that was released on January 1, 2018, but didn’t find their names in the second. Post the Abdul Quddus Judgment names of the kiths and kins of those declared to be foreigner by tribunals but having their name in NRC were also removed. Even the family of a former President of India, Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed did not find mention on the list.

The process is multidimensional with different organisations working together, the NRC, the voters list of the Election Commission, and the Foreigners’ Tribunals with the help of the Assam Border Police, have led to absolute confusion, as these agencies are not sharing information with one another.

With the burden of proof on the person suspected to be the foreigner, the Tribunals seem to be in a record-making spree, racing with each other to declare higher number of foreigners.

A person once declared foreigner is often being put into detention centres without any provision for bail, parole, facility to make phone calls or even any work.

Even though the draft NRC process provides a window for re-verification, due to huge number of people being excluded from the list, it will be very difficult to physically verify everyone. The only course open to them is judicial relief to substantiate their citizenship claim, which is leading to overburdening of judiciary which already reels under judicial pendency.

Asgar Ali is one of those who is left with no recourse now. Ali, a carpenter from West Bengal had never voted or applied for inclusion in any electoral roll in Guwahati. He was a registered voter in Ballygunge, South Calcutta.

One of the grounds on which Asgar was declared to be a foreigner was that the Voter list of 1966 of Ballygunge Assembly Constituency that he submitted, and that conclusively proved his citizenship was issued by the Director of Archive who, the High Court and the Supreme Court ruled, was not the custodian of the document. The fact that a RTI reply confirmed that the Director of Archive was indeed the custodian was ignored by the court. Ali has no idea what the future holds for him.

Deporting people like Ali to Bangladesh is not an alternative given that Dhaka has never accepted that they are its citizens. India has no formal agreement with Bangladesh to drive away the illegal migrants back into Bangladesh. Furthermore, raising this issue can also jeopardise relations with Dhaka. This would not only damage bilateral relations but also denigrate the country’s image internationally.

The other option is large scale detention camps, which are an unlikely option for a civilised democracy like India. An additional option is instituting work permits, which would give them limited legal rights to work but no political voice. But then what happens to people who are not of working age – the children and the elderly?

The complete procedure that is being adopted for determining something as elementary as citizenship is fraught with errors, discrepancies and sometimes even hate.

The Supreme Court in the past did step up to protect a few individuals but many have not been that lucky. The Guardian of Fundamental Rights has many times refused to take a lenient view. The degree of proof seems to be the same degree that is required under Criminal law. A person suspected has to prove beyond reasonable doubt that he is an Indian citizen without any evidence to the contrary being produced by the State Authorities.

(Anas Tanwir is a lawyer practising in Supreme Court)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines