Not by growth alone: Redistribution the key in reducing poverty

World’s poor live in middle income and not poor countries. Reducing inequality and ensuring prosperity for all, argue Nils Enevoldsen and Rohini Pande, need redistribution, a political solution

Recent studies claim that the per capita incomes of developing countries are at last on track to catch up to those of industrialised countries, as policies and institutions in these countries are converging to those of the rich world.

Nils Enevoldsen, an independent research consultant and Rohini Pande contend in this post that this country-level catch-up will not be sufficient to eradicate extreme poverty, as the blessings of this ‘growth’ are not reaching the poor. Inclusive prosperity requires a political solution – redistribution:

Development economists have wondered for decades whether poor countries will eventually ‘catch up’ to the rich ones. Will Afghanistan catch up to India? Will India catch up to Japan? Empirically tested for the first time in the early 1990s (Barro 1991), the evidence was mixed, but overall suggested divergence: rich countries were growing apace, and poor countries were lagging behind, destined never to catch up.

But shortly thereafter another consensus began to form – ‘conditional convergence’, that is, each country was on a trajectory to converge to a certain level of income, but how high a level, was conditional on that country’s policies or institutions.

This remained the consensus for over 20 years – no doubt helped in part by the difficulty of defining ‘institutions’ – but recent works (notably Roy et al. 2016, Patel et al. 2021, Kremer, Willis and You 2021) suggest that the facts are changing. Since the mid-1980s, convergence has been gradually less and less conditional, and since 2000 has even been absolute. These studies argue that prior to Covid-19, poor countries – and especially lower-middle-income countries like India – were on track to catch up to rich ones after all. This seems to be, in part, because underlying policies and institutions in these countries are themselves converging to those of the rich world.

This is welcome news in the fight for economic justice for the poor. However, in a response to Kremer, Willis, and You (2021) we discuss why, welcome as it is, it may not be quite as momentous for poverty reduction as it appears on the surface.

We outline three reasons as to why this might be the case. First, the distribution of world poverty is changing. More of the world’s poor are living in middle-income countries. Fewer poor countries is not the same as fewer poor people. Second, manufacturing is providing fewer well-paid jobs in developing countries than it did in industrialised countries. Redistribution will be essential to spread the benefits from industrialisation.

Third, challenges remain ahead. Redistribution is enabled by democracy, but the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic is abetting democratic backsliding. Meanwhile, climate change threatens future growth (Enevoldsen and Pande 2021).

The distribution of world poverty is changing

Development economists have long concerned themselves with poor households and with poor countries. For much of the discipline’s history, the association was natural – poor countries were predominantly home to poor households, and poor households were predominantly found in poor countries. In this view, finding absolute convergence is reassuring: as poor countries grow, so do the incomes of the poor individuals within those countries. And poor individuals in poor countries make up the world’s extreme poor…don’t they?

The answer is, increasingly, ‘no.’ The period since 1980 has seen a weakening correlation between country income and the share of the world's poor in that country. While country convergence remains unequivocally beneficial for poor individuals, its relative importance diminishes as within-country inequality has begun to dominate between-country inequality.

We argue that absolute convergence in an increasingly unequal world is driving a wedge between country incomes and living standards of vulnerable groups, especially within lower-middle-income countries.

The poor are increasingly living outside poor countries: A common presumption is that poor people live in poor countries, many impoverished by colonialism. This was not always the case. Bourguignon and Morrisson (2002) find that in 1820 almost 90% of global inequality was due to within-country inequality rather than between-country inequality.

This proportion fell in the subsequent century, and by 1950 within-country inequality accounted for only 40% of global inequality. This proportion remained stable for the next four decades. However, in recent decades, the global income inequality decomposition trend has been reverting. Using a different metric, the World Bank (2016) finds that between 1988 and 2013, the proportion of global inequality due to within-country inequality rose from 20% to 35%.

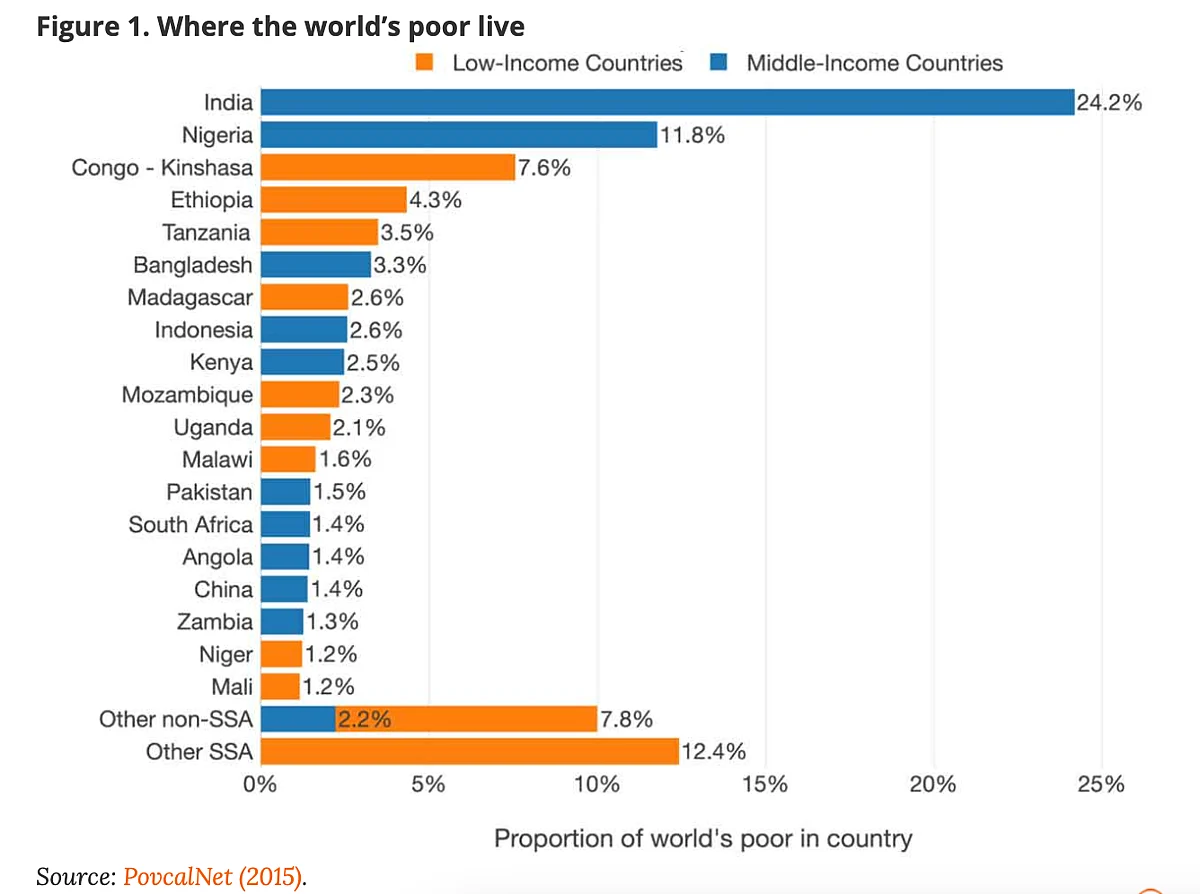

The poor are increasingly clustered within countries: Page and Pande (2018) identify the subset of middle-income countries that contain 1% or more of the world’s poor – high-poverty middle-income countries (HiPMIs). Just five HiMPIs are home to nearly half of the world’s poorest – India, Nigeria, Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Kenya. A quarter of the world’s poor live in India, a middle-income country.

While the average incomes of these countries are not among the lowest in the world, the trends of inequality within them have an outsized impact on the global convergence between rich and poor regions, communities, households, and individuals.

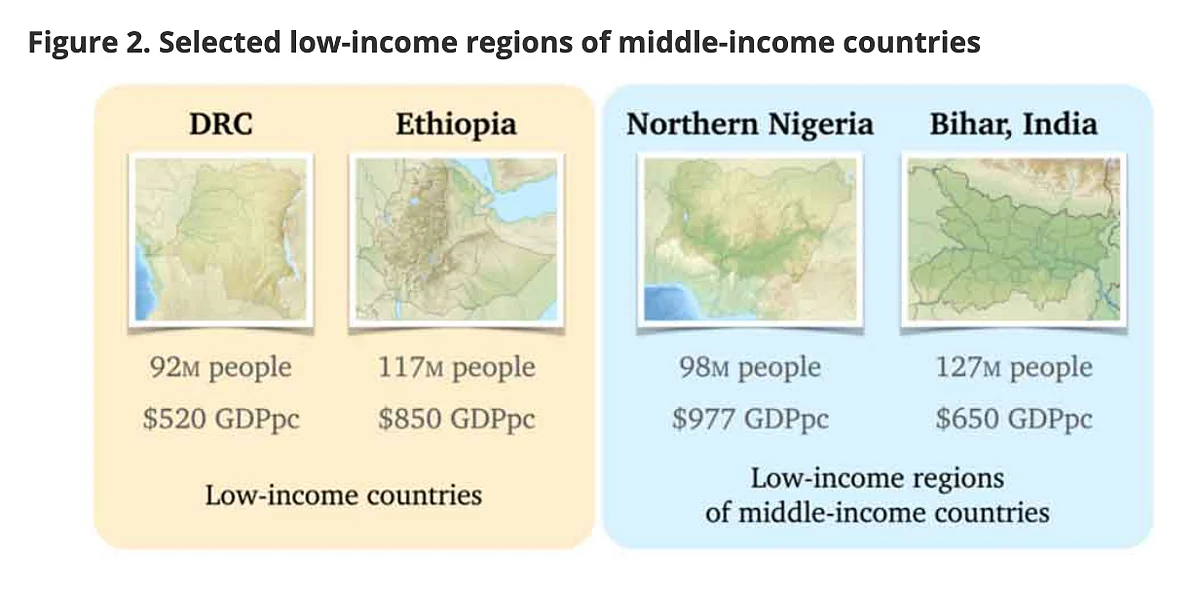

Within HiPMIs themselves, poverty is, naturally, non-uniform. As though viewing a fractal through a loupe, the spatial clustering of poverty so visible on a global scale is replicated within middle-income countries. The distinction between a poor region of a HiPMI and a poor country is not demographic, but political.

In populous middle-income countries like HiPMIs, some such regions are massive. In fact, if the Indian state of Bihar were a sovereign State, it would be the world’s most populous low-income country, with 127 million people and a GDP (gross domestic product) per capita of just US$ 650. Or, were the northern region of Nigeria to break away, the low-income country it became would be second in population only to Ethiopia.

Since such a large proportion of the world’s poor are clustered in so few middle-income countries, the trends of within-country inequality in these specific countries matter quite a lot for global poverty – arguably more than all between-country inequality combined. The trends here are mixed, but are especially concerning in the South Asian HiPMIs of India and Bangladesh, and more or less neutral in other HiPMIs like Nigeria and Indonesia.

Indeed, the same convergence tests that are done between countries can also be done between subnational regions, and here there is suggestive evidence from India of within-country divergence in regional per capita income (Sachs et al. 2002, Ghosh 2008, Ghosh 2012, Kalra and Sodsriwiboon 2010).

Manufacturing is providing fewer well-paid jobs: If poor countries converge with rich ones with respect to average income, then residual poverty must reflect within-country inequality. The important question, then, is whether processes of economic growth that imply absolute convergence are increasing within-country inequality.

Historically, processes of economic development have been marked by a decline in the share of agriculture in both country income and labour employment. For today’s rich countries, the process of structural transformation was accompanied by the manufacturing sector demonstrating a double advantage. It was both more productive than farming, and absorbed a larger population share.

More recently, lower-income countries and HiPMIs have seen relative increases in the income shares of manufacturing, but not so much in manufacturing employment. Service growth shows a similar pattern – India being the exemplar case. Between 1950 and 2009, the share of agriculture in India’s GDP fell from 55% to 17%, manufacturing rose but remained under 30%, while services increased to 57%. Fan et al. (2021) show that the rise in services led to limited employment gains.

Thus, recent trends in manufacturing and services suggest these remain productive sectors that are gaining GDP share in the world’s less well-off countries. But they are less likely to provide high levels of well-paid employment, perhaps because the most productive firms use globally competitive labour-saving technology (Diao et al. 2021). The declining labour share of income in many developing countries may further weaken the link between GDP convergence and household well-being.

Challenges remain ahead

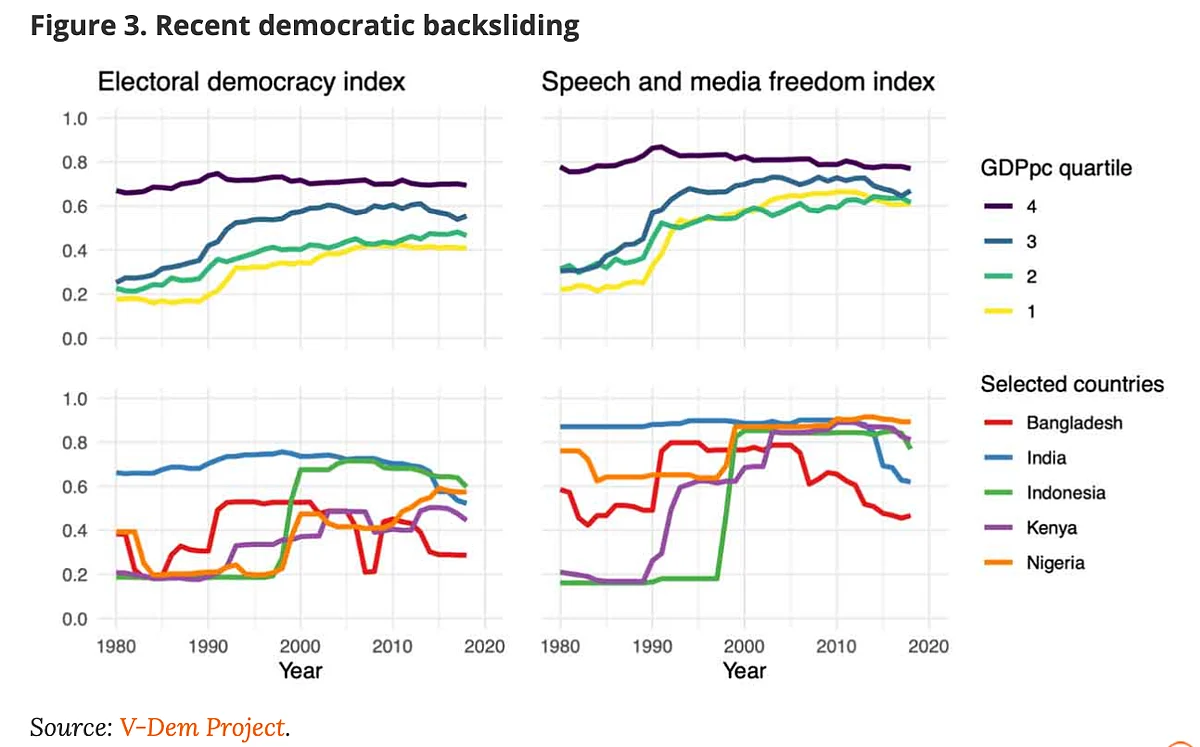

Democratic backsliding threatens redistribution: Dis-equalising growth can still benefit the poor if the State is willing and able to redistribute resources to those who need them. Pande (2020) shows that most of the world’s poor now live in democratic States, but many of these States are relatively non-egalitarian.

The 21st century has, concerningly, been marked by significant democratic backsliding. Haggard and Kaufman (2021) define it as “the processes through which elected rulers weaken checks on executive power, curtail political and civil liberties, and undermine the integrity of the electoral system”. They identify over 16 democracies that have seen such backsliding in recent years.

Covid-19 threatens democratic backsliding

Democratic backsliding and reduced redistribution are particularly costly for the poor and near-poor when economic growth falters – a possibility that has come to pass with Covid-19 in many HiPMIs. The year 2020 was the first year in the 21st century when world poverty rose. The newly poor are concentrated in lower-middle-income countries – 61% in South Asia and 27% in Sub-Saharan Africa (Lackner et al. 2021). At the US$ 3.20 per day threshold, 68% of the newly poor are in South Asia.

Climate breakdowns threaten growth

In the medium term, climate breakdowns will likely constrain fossil-fuel-based growth and this may particularly reduce growth in lower income settings. For the average developing country, economic convergence is accompanied by a convergence towards the global average usage of most primary energy carriers, consumption of final energy in most sectors, and total carbon dioxide emissions. Current economic growth in lower-income countries is no less energy intensive than past growth in industrialised countries (van Benthem 2015).

International climate change mitigation policies are a double-edged sword for poor countries and HiPMIs. If adopted, they will make fossil-fuel-based convergence more expensive. If not, climate change itself may reverse their growth through droughts, floods, storms, or rising sea levels.

Conclusion

Recent research documents a trend towards absolute convergence in GDP per capita and provides suggestive evidence that policy convergence played a role. From a development perspective, it is useful to link the narrative about country-level convergence to income distribution within countries – poor regions, communities, households, and individuals. Doing so highlights the need for institutions that will ensure greater domestic redistribution and, possibly, also a rethinking of domestic industrial policy. This, we argue, is critical if absolute convergence is to be the tide that lifts all boats. The need is amplified by the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic and the increasing likelihood of significant climate breakdowns.

(This post has been published in collaboration with the IGC Blog)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

Published: 12 Nov 2021, 3:57 PM