May, the cruelest month: hunger in the summer of discontent overwhelms Uttar Pradesh

Hunger, no stranger in Bundelkhand, stalks the land again. But now the cocktail of paranoia and prejudice has made it even more volatile

The graffiti on the wall receives scant attention from people. Villagers seem indifferent. Officials cannot care less. They shrug when asked who scrolled the word Bhookh (Hunger) on the wall of the panchayat bhavan, not just once but three times. The local wit can’t resist a wisecrack. “Obviously someone who is hungry,” he says with a sly smile. Nobody laughs.

There is something faintly reassuring in what the wit said. The famed rustic humour is not completely lost in these grim times. But the word Bhookh haunts the outsiders, the well-fed visitors from the city, making them feel a little guilty.

Several people are hungry in village Khera. Shiv Devi is just one of the women who makes the trip every morning to the panchayat bhavan to secure a ration card. Denied even a provisional ration card on one pretext or the other, she returns every day, stoical but anxious. “If we don’t get food soon, we will die of hunger,” she mumbles. Even charity is in short supply. NGOs and civil society efforts are not enough to feed all of them. Shiv Devi has a family of seven to look after, including three children. Most of the time, a neighbour says, Shiv Devi remains hungry so that the children get an extra ‘Roti’ to eat.

Her problem is compounded by the fact that she belongs to a nomadic community. There are 17 such families in the village. They would earlier deliver small, household tools and do odd jobs while moving from one village to another. Their earnings have come down to zero after the lockdown.

Some of them have received the provisional ration card following intervention by an NGO, Vidya Dham Samiti. But Shiv Devi is still waiting.

People laugh and jeer at us, informs Phool Chand. “We cannot even go near the ration shop. People begin to shout, ‘Carona aa gaya’ and a young man once even hurled a stone at us,” he adds. In Khamora village of Banda, even in normal times the ‘Kucch bandias’ as the 70 dalit families are called, were not welcome. Now the fear of getting infected by the coronavirus has made the situation worse.

“The custom of untouchability is increasing; People no longer want to talk or even allow us to enter the village,” says Phool Chand, admitting that Kuchhbandias lived in poor hygienic conditions, next to a sewer.

They certainly are among the poorest of the poor, confirms Raja Bhaiyya of the NGO VDS active in the area. They are also eligible to foodgrains under the PDS but local officials have not facilitated access to food for them,he confirms. A complaint has been filed with the district administration and action is awaited.

Her husband died four years ago, leaving her to feed herself and six children. Two of the eldest sons, though they are still minors and below 18 years of age, went to Pune to work as on daily wages and got stuck there following the lockdown.

Her eldest daughter is paralysed and Chunni had taken a loan to get her treated. But her treatment has stopped. She is waiting for her sons to return. She doesn’t have a mobile phone but has been informed that both sons had started for home.

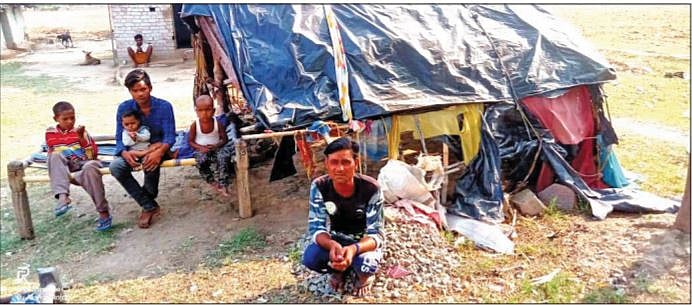

“Perhaps they are walking or they might have hitched a ride on trucks,” she says. But she is certain that she would never again allow her sons to leave home. We will live and die here, she says, “they will not die in pardes’. Manish, however, is regretting the decision to return. He used to work in a utensil making factory at Jagdhari. But after walking and hitching rides to reach home, he was quarantined for 14 days with others under a shamiana with a black, tarpaulin cover.

But even after the quarantine period is over, he is still treated with suspicion. He was assaulted when he insisted on fetching water from the village hand pump. Passing policemen rescued him. But he was let off with a warning. “Never visit a public place”, he was told.

“This lockdown has alienated me from the village. These are the same people with whom I grew up and now I am nobody to them. They are treating me as if I am untouchable,” he fumes. His is not a stray case. A few days back, a fight broke out between another returnee and villagers. The returnee had gone to a shop to buy biscuits for his children and inadvertently touched the counter. He was beaten up with lathis and had to visit the local doctor for medical aid.

“We are not covid positive,” Manish said. “We are being kept in isolation for precautionary measure. But the whole village treats us as covid patient,” he said.

The ground situation in Bundel khand is grim. But the situation elsewhere in Uttar Pradesh cannot be much better. Many of the villagers had never heard or known about lockdowns and coronavirus. They still don’t. Irrational fear stalks them and the returnees are bearing the brunt of their suspicion. It is a tinderbox, ready to explode.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines