Lok Sabha seats delimitation: Will the 'progressive' South get a raw deal?

The new parliament building holds hints that the BJP plans to take advantage of the South’s success at population control as the region may get less seats than the more populated Hindi belt

The new parliament building with enhanced seating capacity for the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha has revived apprehensions in the South over the next delimitation exercise.

Delimitation is the process of fixing the boundaries of territorial constituencies for a legislative body. National delimitation commissions have been constituted four times in the past—in 1952, 1963, 1973 and 2002.

While there has been a freeze on delimitation of constituencies till 2026, it will require a new census (India skipped the 2021 census on the pretext of the pandemic). It is not clear if the government plans to wait for 2031 to conduct the census, which normally takes place after a 10-year gap, or whether it will initiate one earlier.

With population the dominant factor for delimitation of constituencies, and each Lok Sabha constituency expected to have roughly similar numbers of voters, the more populous northern states—such as Uttar Pradesh and Bihar—are likely to gain many more seats. The present strength of the Lok Sabha is 545; the new parliament building provides for 888 seats.

Correspondingly, the southern states stand to lose seats because of, ironically, better success with population control. The already skewed power equation, fear the southern states, will put the South at a greater disadvantage with reduced representation in the Lok Sabha—and consequent loss of influence in policymaking.

This is widely perceived as unfair because, as Bharat Rashtra Samithi (earlier Telangana Rashtra Samithi) working president K.T. Rama Rao said last week, the southern states of Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Telangana should not be penalised for following progressive policies, controlling population growth and advancing on human development indices.

“With only 18 per cent of the country’s population, the southern states have been contributing 35 per cent to the country’s GDP, and the proposed delimitation based on population is a gross injustice to them,” he said.

There is a rising clamour for weightage by state in the South as delimitation per population alone is perceived as irrational and unjust, because the ruling BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party), would welcome the South’s loss of political clout. The BJP itself has miniscule representation in the Lok Sabha from states south of the Vindhyas.

A provision in Delimitation Acts from 1952 onward, per officials who carried out delimitation in Jammu and Kashmir (finalised in May 2022), does provide for factors other than population—like physical features, boundaries of administrative units, communication facilities and public convenience—to be taken into account while drawing constituency boundaries. Its usefulness remains clouded, however, as the delimitation exercise met with severe criticism from the National Conference and the PDP (Peoples Democratic Party), the two valley-based parties, which held political factors had influenced it.

Shiv Sena (UBT) Rajya Sabha member Priyanka Chaturvedi said the concern also held for Maharashtra in the western region, as it has successfully mitigated population growth. Calling it a “massive question”, she says, “The government cannot be unfair to the South while states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar have been unable to match the growth story in terms of economic development, welfare schemes and population control.”

She suggests giving weightage to social welfare mechanisms and proportionality to economic growth. Chaturvedi adds, “The South cannot be the beast of burden of India. Maharashtra is the highest taxed state, but gets minimal returns from the Centre.”

Actor and Makkal Needhi Maiam founder Kamal Haasan voiced the angst of the people when he said South India should not be punished for good behaviour. “I am a centrist, my concern is about India… For me, India is first, but southern states have to come together and have a dialogue on how the nation should move forward,” he said at the India Today Conclave South 2023 in Kerala on 2 June.

The issue has triggered discussions on the widely acknowledged North–South divide, with many arguing that the southern states are already losing out in the evolution of funds to states and in representation in the Union cabinet.

The delimitation of Lok Sabha seats was last done in 1971. A. Narayan, professor at the School of Policy and Governance, Azim Premji University, says the next such exercise after 50-plus years would drastically reduce the number of Lok Sabha seats down South if the basis is population alone.

“There is already a widely prevalent sense of injustice and the belief that whichever political party is in the saddle in New Delhi tends to use central agencies to browbeat the states,” adds Narayan. He believes a public debate should precede the exercise to determine the weightage of each factor applied.

Linguist and cultural activist Ganesh Devy, however, believes that even states like Gujarat and Odisha will lose some Lok Sabha seats if the exercise is executed on the basis of population alone. “Gujarat will be the worst-hit due to outward migration. There is expected to be a public outrage and one does not know how Prime Minister Narendra Modi will contain it,” he says.

Per Devy, this is not a North–South divide but one between states with large migratory populations and those without. States like Uttarakhand, which has five Lok Sabha seats, might also lose one or two seats as a large number of its original inhabitants have migrated to New Delhi, he says.

Similarly, many youth from Telangana have migrated abroad to take up IT jobs, while Kerala’s population has spread further afield due to shortage of land. In Uttarakhand, the divide is also between the hills and the plains. When the state was carved out in 2000, the hills had 40 seats in the state assembly of 70.

The first delimitation in 2002 already saw seats filled from the hills come down to 34 due to migration. It is feared that the next delimitation will reduce the hills’ representation further, yielding greater influence on state policies to the plains.

In 1976, the then-prime minister Indira Gandhi suspended the revision of seats until after the 2001 census. In 2001, Parliament extended this freeze until the next decennial census after 2026, which indicates it is now scheduled for 2031.

So even if population is not the sole factor, it is expected that legislators and policymakers will need to factor in demographic and sociopolitical changes over the past 60 years, given the time elapsed.

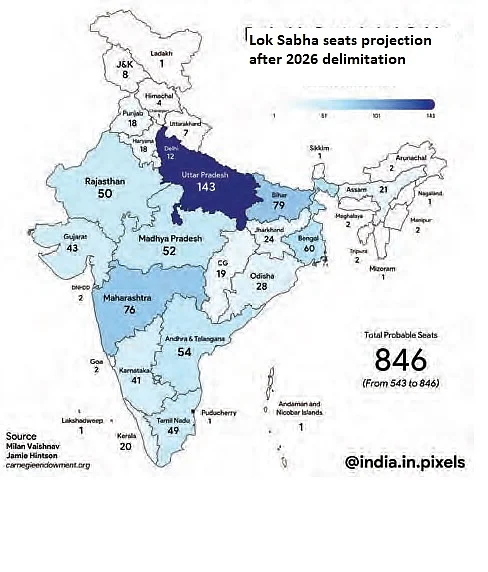

An independent study done by Milan Vaishnav and Jamie Hintson of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace during the 2019 Lok Sabha polls estimated that four north Indian states (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh) would collectively gain 22 seats, while four southern states (Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Telangana, and Tamil Nadu) would lose 17 seats.

‘Based on our population projections, these trends will only intensify as time goes on. In 2026, for instance, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh alone stand to gain 21 seats, while Kerala and Tamil Nadu would forfeit as many as 16,’ the report said.

The study further projected that if the strength of the Lok Sabha increased per projected population figures, the Lok Sabha would have to have a strength of 848 to enable accurate representation according to the proportion-to-population principle. In such a scenario, Uttar Pradesh will have 143 Lok Sabha seats as opposed to the current 80, while Kerala will still have the same 20.

Former chairman of the Karnataka legislative council B.L. Shankar, who wrote a doctoral thesis The Indian Parliament: A Democracy at Work, recalled that when delimitation for assembly seats in Karnataka was done in 2008, there was a demand that for constituencies in the Western Ghats and Malnad regions, the yardstick should be geographical area and not just population.

The North–South divide, says Devy, also stems from differences in language, state structure and philosophical foundations, says Devy. The basis for civilisation in the South was Dravidian and Tamil, unlike in the North, he notes. Secondly, rules in the South, even when they were Islamic rules, were in accordance with local traditions. The institution of kingship in the South also developed locally. The third difference, he says, is that Hinduism in the South is “philosophically deeper” and not just a “populist idea”.

He adds, “Hinduism is a spiritual identity in the South rather than a religious identity. That is why social reformers like Basavanna and Sree Narayana Guru became possible.”

The delimitation will sharpen the existing divide, he feels. “Since the worst hit due to delimitation will be Gujarat, we have to wait and see how Modi convinces the people of that state,” he asserts.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines