Despair and hope: Waiting for elections in Jammu and Kashmir

Kashmiris desperately want the election to be held. Most Kashmiris do not think an election is imminent. The state-turned UT has been without an election for three years and without an assembly

The tricolour fluttering atop the clock tower at Lal Chowk, the serene Dal Lake in Srinagar and tourists crowding Pahalgam and Gulmarg reinforce the ‘All is well’ narrative. The once regular curfews are now history. Flash mobs pelting stones at security personnel are also missing. Srinagar is calm and as beautiful as ever.

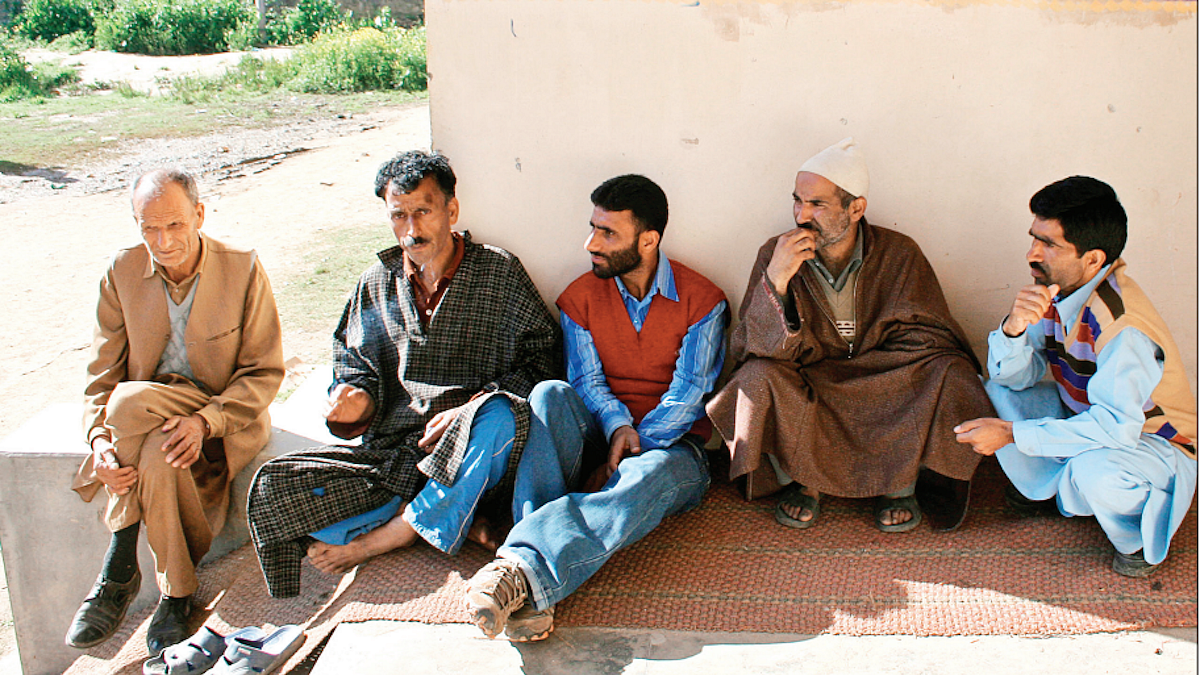

What can be wrong? It is only when one ventures into the back lanes that one hears voices venting their frustration at excesses and a longing for the assembly election. Kashmiris desperately want the election to be held.

Most Kashmiris do not think an election is imminent. The state turned-Union Territory has been without an election for three years and without an assembly. But even separatists and those who earlier had boycotted elections are keen to have the election soon. It is not because their faith in democracy has suddenly gone up. But it is because the election, they hope, will put an end to the ‘authoritative apparatus’ that has stifled them.

Feeling the absence of political representatives

With no elected government in place, “officials are far more abrasive and arrogant than ever; and the Lieutenant Governor is not accessible to most of us. In any case one cannot approach the Lt. Governor for everything. We have nowhere to go,” says Imran Gilani. “The Lt. Governor isn’t as accessible as my local legislator was,” elaborates Abrar Khan of the J&K Traders Association.

The next election, they predict, will see a heavy turnout of voters. There are fears about the election. Everyone believes that the election will be rigged and a puppet regime will be installed, says Rauf Butt of the PDP. But still polling will be high because people would like to have some local representative to whom they can turn.

The fears are not unfounded, says Rashid Dar in Anantnag. The way in which Sajjad Lone, Altaf Bukhari and now Ghulam Nabi Azad are being promoted is quite evident, he says. “Altaf Bukhari was provided funding, a large office, security cover and everything he needed to establish J&K Apni Party,” he points out.

He has no doubt that others like Azad too would not suffer from lack of resources. Butt fumes, “Who is Altaf Bukhari and what is the background of Sajjad Lone?”

Even Sanjay Sarraf, spokesperson of the National Lok Janashakti Party (NLJP), an NDA ally, raises similar concerns. Sarraf, a prominent voice among Kashmiri Pandits residing in the Valley, says “Despite opposition from the political class, the common man didn’t resist the changes in August 2019 and accepted the bifurcation of the state.” But promoting people like Lone and Bukhari could fuel discontent, he feared.

Beyond politics

One can sense growing disenchantment among people since business and employment opportunities have remained stagnant. Record tourist arrivals helped but little else has happened to give a boost to development and employment. The construction of the Ramban-Banihal road and tunnel remains the only mentionable achievement of the government, said several people.

“We were doing quite well before 2019 and our average income, our quality of life and life expectancy were far better than most parts of India,” says Zubair, a businessman in Kulgam.

The abrogation of Article 370 should have been followed by swift development and quick election, says Sarraf. Surendra Singh Channi, Congress spokesperson and a prominent leader of the Sikh community, admits that the security situation has improved. But growing frustration over the economy and unemployment can change the situation quickly, he adds.

Looming economic crisis

Santosh Mahto has been travelling to Kashmir from Dumka in Jharkhand in search of work for the past 15 years. “After the tourist season ends, there are maintenance and construction activities. I work for three to four months here and remit between one and two lakh rupees to my wife’s account every year,” says Mahto.

While travelling south from Srinagar, one comes across large number of people from Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Bihar, Odisha, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh. Most of them work as domestic helps, construction workers, drivers, transporters, working in orchards, in shops and in farms. They are mostly Dalits, tribals and from backward communities.

These migrant workers are an integral part of the local landscape now. People say Kashmiri middle and upper middle class cannot survive without them. “But politics has made our lives miserable and uncertain,” says Ramcharan Gondi, a construction worker who is also from Jharkhand’s Dumka district.

“We were never targeted by militants during the peak of militancy in the 1990s,” claims Gondi. But during the last three months at least five migrant workers have been killed. This wasn’t due to any hostility following the bifurcation of J&K or the abrogation of Article 370. Nor is there any hostility or hatred for the so-called outsiders among Kashmiris. But provocative and unwanted political slogans, meant to appease voters elsewhere, have directed militants’ ire to the migrants, claims Rauf Butt of PDP.

Statements hinting at ‘Voting rights for the outsiders’, ‘resident status for people from other states’, ‘voting rights for security personnel and officials posted in Kashmir’ etc., though denied officially, have done the damage. “It created the sense that the government in Delhi is trying to impose a non-Kashmiri rule on locals”, says Mairaj, a journalist.

“I have been visiting the state for the last 13-14 years. Never saw people looking at us with suspicion. Now they ask whether we plan to stay here or go back home,” says Ram Khilawan, a labourer from Ballia working in Ramban area.

The security situation

Political workers you speak to invariably blame “agencies” and the “larger conspiracy” for stone pelting incidents that kept the pot boiling. Stone pelting benefitted certain people in power, they say.

Notwithstanding conspiracy theories, people seem to be genuinely relieved at the disappearance of flash mobs. “It was risky to move in private vehicles then,” says Askar Ahmed in Srinagar.

But security threats continue. “Even militants have been using small handguns, made-in-China pistols and revolvers, which are even more dangerous as both people and security personnel are caught unaware,” says Channi.

Fear will not go away unless trust is restored. More people-centric policies to restore people’s faith in the administration and in each other are what is needed, say Kashmiris.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines