1980s: The over looked decade, the decade when India began to change

While the decade of 1990s is credited for ushering economic reform, people tend to overlook the fresh ideas that marked the 1980s

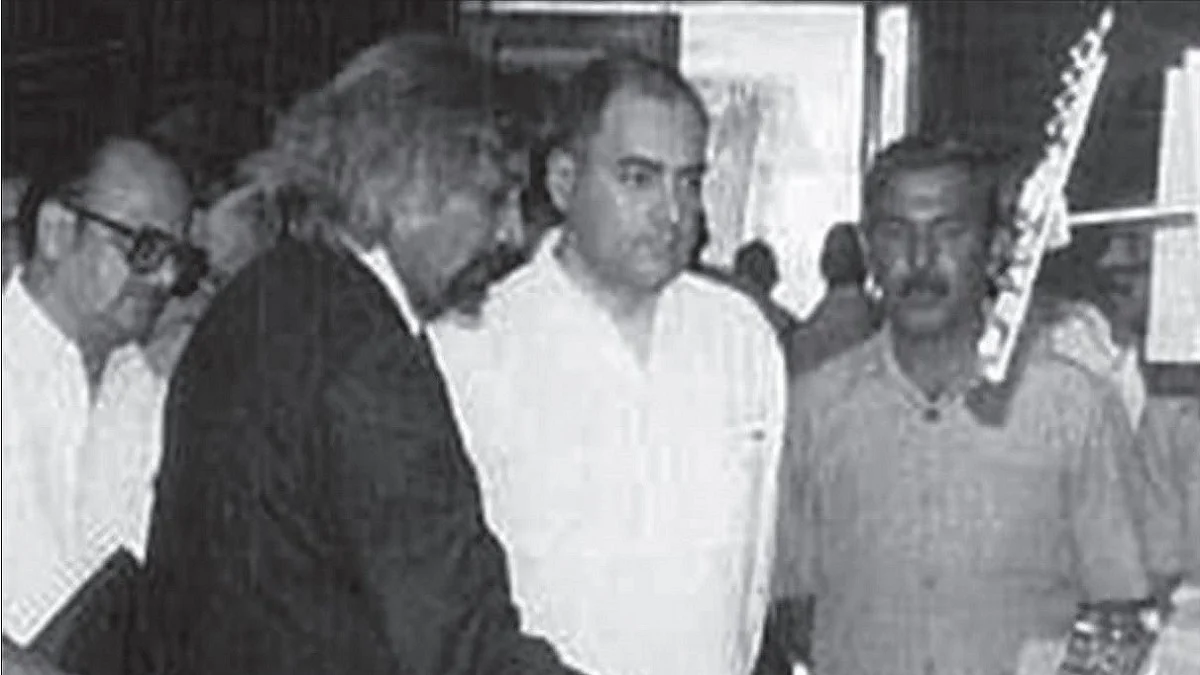

I n our post-Independence history, the 1980s is generally remembered for all the wrong reasons. The first half was marred by the Khalistani movement and the violence in Punjab, followed by the assassination of Indira Gandhi and the massacre of the Sikhs in Delhi in 1984. The Rajiv Gandhi years are largely remembered today for the Bofors scandal, which marred the good start and fresh thinking he had brought into the country. The 1990s, on the other hand, is widely acknowledged as the beginning of the new era because of the economic reforms initiated in 1991.

But perhaps it makes sense to re-examine the 1980s. As I pointed out in a recent column, the seeds of the growth of the automobile sector, which is considered India’s most successful manufacturing story, was actually sowed by policies taken in the 1980s.

The birth of Maruti which was allowed collaboration with Suzuki, allowed to set an initial production capacity of 100,000 cars (when others were producing 20,000 or so) and forced to indigenise 75% of the auto components by 1988 helped create the modern auto component vendor ecosystem that later entrants who came in after the reforms of 1991 could capitalise on. The fact that Maruti also got a protected domestic market for almost a decade helped it complete its task. (This is not to take anything away from the excellent management it had).

The two-wheeler story was even better. The government gave out licenses for 100 cc motorcycles to four players, who were allowed to form joint ventures or get into technology partnerships with global manufacturers. They tied up with Honda, Kawasaki, Suzuki and Yamaha, bringing modern commuter bikes to the country. Most importantly, they were allowed to set up capacities that allowed for economies of scale. This allowed them to grow, flourish and reinvest in better manufacturing practices and technology.

Meanwhile, in his recent column in The Indian Express, Amartya Lahiri also touches on the contribution of the Rajiv Gandhi government of the 1980s. As Lahiri points out, Rajiv Gandhi’s government allowed industrial de-licensing and relaxed capital goods imports. These, and other policies, led to a growth spurt which saw GDP growing at 5.2% during the 1984- 91 period.

The contribution of the 1980s policies, both the good and the bad, actually needs to be studied in greater detail. Without taking away any credit from Prime Minister P V Narasimha Rao and his finance minister Dr Manmohan Singh, who ushered in the economic reforms that led to free markets, globalisation and a spurt in economic growth, their work would perhaps not have been possible without both some of the initiatives as well as some of the mistakes of the Rajiv Gandhi government.

Consider the good bits first. The Rajiv Gandhi government welcomed technology, especially information technology. That, coupled with industrial de-licensing and somewhat relaxed capital control, contributed hugely to the setting up of larger scale manufacturing facilities with modern processes and latest technology and also increased domestic competition, removing the near monopoly that companies with prized licenses enjoyed till then.

It is important to note here that in most cases this still did not mean large scale production and global standards. Indeed, far too many Indian businesses were simply not used to really large scale thinking, except perhaps Reliance Industries. Which was why, few of them could take advantage of the new policies.

But the Rajiv Gandhi government policies allowed the Indian computer industry to really find its feet. It started with hardware assembly initially with Hindustan Computers Ltd (HCL), Wipro and a host of others growing rapidly as the country adopted the PC. This in turn would help the software and software services industry develop later.

Equally, telecom infrastructure got a great boost through the STD booth system though it seems horribly primitive by today’s standards.

In fact, for anyone old enough to remember, the conditions pre-1984 and conditions post-1984 were remarkably different.

But ironically, the reforms of 1991 would probably not have happened without the mistakes of the Rajiv Gandhi government which ran up deficits and kept monetising them. Reserves had been falling steadily since the beginning of the 1980s and debt, including external debt, had been going up. Political uncertainly following the Bofors scandal, the Gulf war and liquidity problems helped create the perfect storm.

It can be argued that if the Rajiv Gandhi government had not been lax about falling foreign exchange reserves and fiscal deficits, the Indian government would have continued in its closed economy path for a few more years. It was the crisis which forced the P V Narasimha Rao government to take a path it might not have taken if it had not inherited the problem.

(Prosenjit Datta is former editor of Business world and Business Today magazines. This column had first appeared in his blog Prosaicview)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines