The 28th Kolkata International Film Festival features ‘Rare Language Films’ and long queues

Prior to 2012, the festival was limited for viewing to certain dignitaries and ‘invitees’. Only in 2012 did it open up to the masses

What started off as simply Kolkata Film Festival in 1995 and diversified to include the ‘International’ in 2012 for its 18th edition, is now one of the largest film festivals in India.

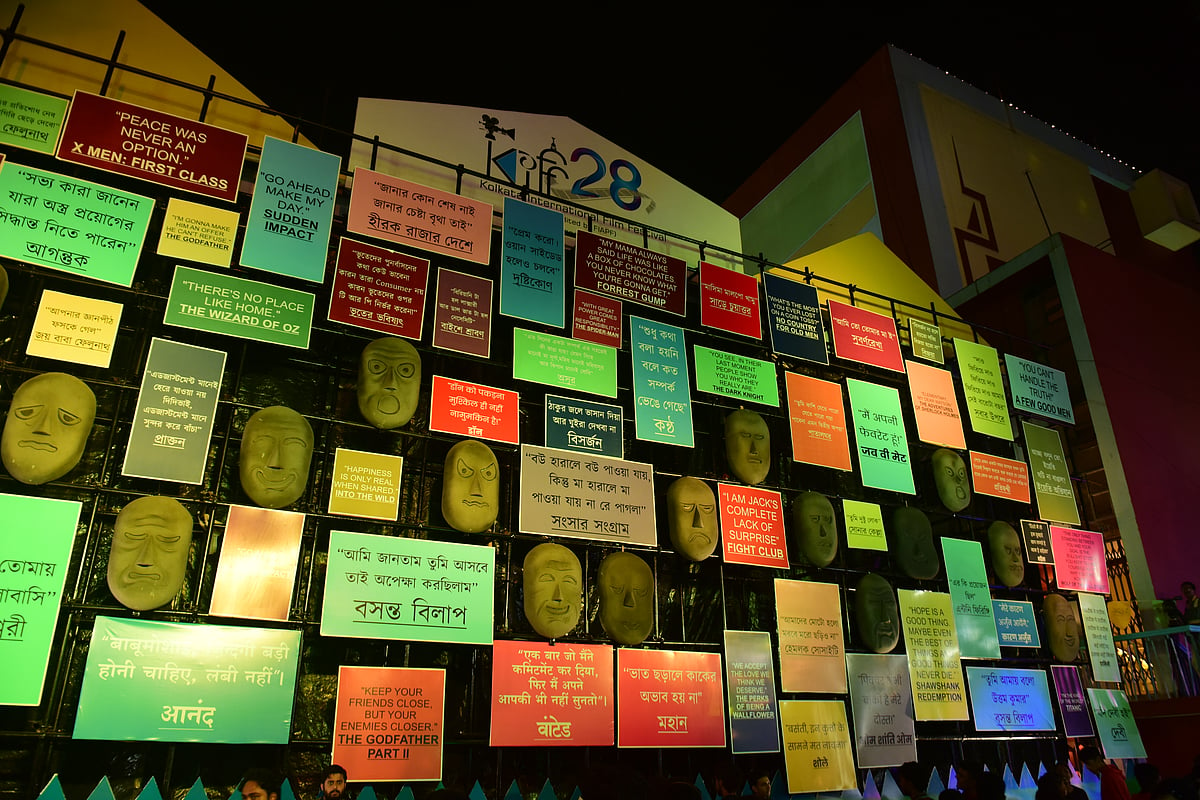

Prior to 2012, the festival was limited for viewing to certain dignitaries and ‘invitees’; only in 2012 it opened up to the masses. The 28th edition of KIFF kicked off on December 15 and will go on for a week till December 22, 2022. A total of 465 films are being screened this year – the most number of films to be screened at the festival. Screened across 10 different venues, the theme of this edition is Navarasa or the nine distinct emotions of the human experience.

A large installation at Nandan displays clay sculptures emoting alongside boards displaying iconic dialogues from the most renowned films of all time.

Unheard India: Rare Language Films

Amid the lengthy list of films being screened this year, a striking addition called ‘Unheard India: Rare Language Films’ attracts audience attention. It features films in aboriginal languages such as Rajbanshi, Kurmali and Santhali from host state West Bengal itself, other regional languages such as Maithili, Byari, Sanskrit and Rabha. These films highlight stories and filmmakers from oft-invisibilised communities.

‘Hidden gems’ such as Lotus Blooms, Dharti Latar Re Horo, Tusu, Dhairya, Mansai, Bhagavadajjukam, Nasimay were screened under this category. These films portraying the trials and tribulations of marginalised communities are audience-favourites at KIFF, despite being otherwise unheard of by the larger Indian audience and unnoticed by mainstream media.

Most of these films are directorial debuts. For instance, the Kurmali film Tusu comes from first-time director Biswait Roy, who remains largely unheard of to this day. There are hardly any traces of Tusu on the internet and KIFF provides the first large platform for the film.

Some directors belong to the community themselves. The Rajbanshi film Mansai by Ashutosh Das tells the survival story of a common man from the Rajbanshi community. Rajbanshi is one of the dominant languages of northern West Bengal and yet films made in the language are scanty. Das, a teacher by profession, is a Rajbanshi himself.

Similarly, director Shisir Jha's Santhali film Dharti Latar Re Horo revolves around a tribal couple coping with the loss of their daughter in the Uranium Mining area in Jharkhand. Jha worked on the film for three years, and his film brings out the reality of the Santhals who are mine-workers – a narrative that is being portrayed on screen for the first time.

National Award-winning filmmaker Hiren Bora’s Rabha film Nasimai is the only film being screened from the North East. Rabha is a complex Sino-Tibetan dialect spoken in the regions of Assam and West Bengal.

Pratik Sharma’s Maithili film Lotus Blooms portrays the emotional development of a mother and her child at the intersection of nature and language. Also screened at the Indian Panorama section at the International Film Festival of India (IFFI) this year, the film has garnered positive reception from film-festival goers. “Cinema is not about commercialism; it is about emotions that connect with the audience. Regional films truly reflect the essence of India,” says Sharma.

“This is the beauty of the Unheard India section at KIFF. Cinema from lesser-known languages reaches cine lovers and through these films, the local folklore and fables are also documented," says Santanu Ganguly, the curator of the Unheard India category.

Speaking at the Satyajit Ray Memorial Lecture at Sisir Mancha on December 18, National Award-winning filmmaker Sudhir Mishra also highlights the significance of state-backed support for independent lesser-known filmmakers.

He tells the audience that “rising up” in the age of OTT is an arduous task for an independent filmmaker. “The West Bengal government should help set up a fund to support aspiring independent filmmakers,” he prescribes as he draws from Ray’s advent into cinema.

“Satyajit Ray's Pather Panchali was possible because the then government stepped in. Young people need advice from the right people, they need to be pushed and promoted. The government should set up a fund, which has been done in a lot of countries,” he adds.

Long queues for 'Joyland' and more

“This is the re-opening of KIFF as it was before pre-pandemic. The crowd is unprecedented as you can see,” Punam Roy, a senior KIFF committee member, tells National Herald while attending to reams of curious audiences looking for brochures, the day’s schedule, directions to halls, and most importantly passes to watch Joyland.

“Joyland is completely sold out, it was sold out in minutes,” says Roy referring to Saim Sadiq’s 2022 Urdu and Punjabi-language film which was released and later banned in Pakistan. The film revolves around the life of trans-woman and her affair with a cisgendered man, it became Pakistan's first-ever entry to the Academy Awards, also screened at the Cannes Film Festival this year.

“Pakistan deemed this film to be highly objectionable and banned but our audience at KIFF is relishing every moment of this ground-breaking film,” adds Roy.

The overarching theme of this year, however, are the long and “painful” queues for every adjacent hall. Well into the fifth day of the festival, audiences complained about having to spend hours just standing in line and later being denied entry into the screenings since halls are already “housefull”. Several attendees of the festival had registered for ‘delegate passes’ in July and were still having to queue.

“We are standing here for half an hour only to watch the Swiss-film Neighbours, we have to wait till the previous show ends. We planned to watch more films but that doesn’t seem possible looking at the massive lines,” says Debdeepa Ganguli, who’s been attending KIFF for the past 10 years. Interestingly National Herald spotted the director of Neighbours, Mano Khalil, standing in line to catch a screening post talking about his film to the press.

Meanwhile, at the outset of the 28th KIFF, conversations around the increasing “commercialisation” of the festival emerged. Film critics and makers, such as Judhajit Sarkar, Saibal Chatterjee, Samik Bandyopadhyay and others raised concerns around the festival, which was originally crafted around arthouse cinema, falling prey to the “glitz and the glamour” of the mainstream film industry – transitioning from “classy to massy”.

However, internationally renowned filmmaker Gautam Ghosh, also a jury-member at KIFF defends the recent commercial developments by saying that “it is a conscious decision by the new government to open KIFF to the public and give it a touch of glamour that connects with the masses.” Ghosh believes that KIFF’s current structure and concentration places it at par with international festivals like Cannes, Berlin, and Venice, but rooted in India’s culture and values.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines