Picture Books: A child's toolkit for a difficult world

Imagine how resilient and engaged a generation can be when they have the vocabulary to navigate through life in all its hues. So why not rewrite Red Riding Hood once again?

A good picture book makes a child imagine all kinds of alternative realities. A great picture book does that while also making adults rethink existing realities. There is no denying that stories have agendas, sometimes hidden, sometimes blatant. Stories also have the power to capture the socio-cultural fabric of the time in which they are being told. Why is this relevant? Because with the world changing so rapidly and so dramatically, we need to stay abreast and, as adults in the lives of children, we must prepare the ground well for them to walk with care, comfort and agency.

This may sound a tad esoteric, so let me explain with an example. The ever-popular story of Red Riding Hood has been retold many times over. The story we have all grown up listening to is the 19th century Brothers Grimm version, in which the little girl is rescued by a huntsman. With women being the subordinate gender at the time, the story led us to believe the same.

Roll back a few centuries, however, and the same story in pre-17th century Europe has the little girl using her intelligence and independence to rescue herself by cleverly asking the wolf permission to step out of the hut to defecate—and scooting! Jump to the 21st century and Roald Dahl has the hooded girl whipping a pistol out of her knickers and shooting the wolf down. Each version reflects the time in which it was written.

Today’s children are growing into a world where social norms are being redefined every moment; where identities—social, cultural, political, religious, personal—are being looked at through various lenses and filters; where inclusivity and social justice are imperatives, not preferences; and where the climate crisis is a lived reality, not a bookish definition. In order to prepare our children to live with empathy, integrity, and a sense of ownership, we must start talking to them young.

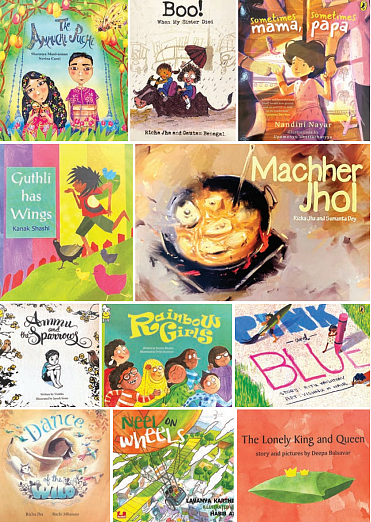

That conversation begins with picture books. Contemporary Indian children’s literature is taking more risks and confronting tougher questions through the picture books being published. For instance, new titles that address gender stereotypes and question heteronormative expectations in the most nuanced manner include Guthli Has Wings and Soda and Bonda (Tulika), Rainbow Girls and Rainbow Boys (Pratham), The Boy Who Wore Bangles (Karadi Tales), Pink and Blue and Ritu Weds Chandni (Penguin), The Unboy Boy and The Dance of the Wild (PickleYolk).

Sometimes Mama, Sometimes Papa (Penguin) and Ammu and the Sparrows (Pratham) are two books about divorce. The first unfolds through the simple and realistic point of view of the child of separated parents, and the curiosity of friends and folk around them. Ammu addresses the anxieties of a child dealing with the struggles of parents headed towards separation through the well-chosen metaphor of waiting, with patience and trust, for little birds to visit a feeder. Talking about different family structures, titles that wonderfully illustrate ideas of adoption are Whose Lovely Child Can You Be (Karadi Tales), In My Heart (Penguin) and the all-time classic The Lonely King and Queen (Tulika).

I know a child who gave out these books as return-gifts at her birthday party, the year she was told by her parents she was adopted, simply because she wanted her friends to stop whispering about it!

As an educator, I have used these books extensively in schools, especially for conflict resolution. I’ve had children read the relevant books, and collaboratively find ways to ease their differences. I have personally seen how picture books can be perfect ice breakers. On one hand, they empower the teacher to begin difficult conversations, with the objective of equipping children to deal confidently with difficult situations. On the other, they empower the child to think critically and derive meaning beyond the basic plot of the story. Parents, too, draw immense courage from such books, and can begin talking to their young ones about the ‘messy stuff ’ without having to wait till they are older.

Over the last decade, I have worked with several schools, supporting them to become inclusive. While a school can easily make infrastructural changes to accommodate children with disabilities and bring in special needs experts to work directly with them, the most challenging part of this transition is the mindset of all the other stakeholders—teachers, support staff, classmates and their parents. To bring a change in the culture of the school at large is the trickiest part. And this is where picture books become magical gateways that let these ideas walk right in. Take Neel on Wheels (Duckbill), for instance, which showcases with lightness and joy that a ‘wheelchair can enable’ without having to hammer home the disability. Or Why Are You Afraid of Holding My Hand (Tulika) and Machher Jhol (PickleYolk Books) which show disability as simply another way of being, rather than an impediment.

Another very difficult topic to broach is sickness and death. For a young child to talk about death is taboo. When a child says to a grandparent, “When you die, will I have to sleep alone?” or to a mother, “When you die, can I take your perfume bottle?”, well-meaning adults invariably intervene with an aghast, “Shhh, don’t say that!” In such a context, Boo! When My Sister Died (PickleYolk Books) is one of the most moving and boldly written books that mark an absolutely admirable and commendable leap. The latest title from the same publisher, Aai and I, is about a child exploring her identity through her mother’s journey of cancer treatment. While books like Gone Grandmother (Tulika), The Ammuchi Puchi (Penguin) and My Two Great-grandmothers (Pratham) approach the subject of losing a grandparent with sensitivity.

Stepping into adulthood without a toolkit to negotiate its complexities can often ease the slide into complacency and passivity. Imagine how resilient and engaged a generation can be when they have the vocabulary to navigate through life in all its hues. Picture books can provide this vocabulary from very early on. So why not rewrite Red Riding Hood once again? What will it be this time? Will she prefer to be referred to as ‘they/them’? Will she be wearing rainbow colours instead of red? Or will she be writing a petition on behalf of the wolf who has to eat little children because the forest is being cut down and he has no other means of surviving

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines