Kochi Biennale 2023: The unbearable lightness of seeing

Visceral responses to an immersive and tactile experience of art and installation

After two years in lockdown, I find myself having a heightened response whenever I experience art beyond the screens in my bedroom. To my occasional embarrassment, tears spring to my eyes every time I visit an art gallery or hear live music—even if it’s by the cover bands that terrorise the neighbourhood whenever there is something to celebrate.

The Kochi Muziris Biennale, a contemporary art festival showcasing work by dozens of brilliant artists in different mediums was, therefore, an utterly overwhelming experience.

For four days, I walked from venue to venue with my family, in wonder. Trying to take in as much as we possibly could, we had to admit defeat in the evenings when our feet protested and our minds gave up being able to process what we had seen. Though we had put aside a few hours on the final day to revisit works that had especially captured our imaginations, it was not nearly enough.

If I could, I would spend days with a single exhibit. My mother and I spoke about the unique quality of visual art that allows this kind of experience, where the audience can choose where to look, and for how long, as opposed to a musical recital or a piece of theatre with a defined beginning and end. (Even the videos at the Biennale played in a constant loop, creating that peculiar and particular freedom.)

Something that I found myself occupied with over the course of the festival was the question of the physical space art lives in. Most of the pieces that excited me were very tactile and kinetic, playing with the spaces they occupied. Even as I flip through the festival catalogue now, I can almost relive the experience of stepping into each room, full of intention and mystery.

In the very first space I entered, I walked through a curtain of bells. This was Haegue Yang’s ‘Sonic Droplets’, where the folklore and ritualistic practices that were visually depicted on the wallpaper really came alive through touch and sound.

The question of space was followed closely by the question of belonging. Who or what belongs? And what is hidden, buried, or pushed out by time, space, and frames?

Using discarded tools, kitchen utensils, and wrestling equipment, Archana Hande created a carefully protected space, ‘My Kottige’. The space could not be entered, only parts of it glimpsed through windows, spyholes, and moving cylinders. The effect was magical, like something straight out of the stories my sister and I had loved, growing up.

From window to window, we discovered more and more of ‘My Kottige’, laughing at each other in mirrors and pointing out things the other had missed. Reading about it afterwards, I was fascinated by the significance of the material and past lives of the found objects—though most of them come from starkly different spaces, with different gendered and social connotations, they are all made of cast iron, and now coexist in Hande’s work.

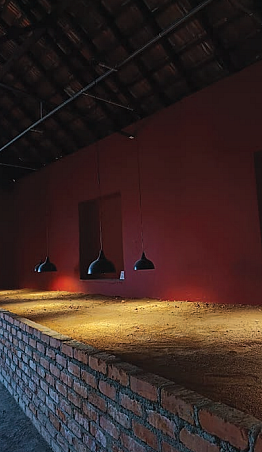

Another piece I remember vividly is Amol K. Patil’s ‘The Politics of Skin and Movement’. In a room, there is an expanse of sand. Lights single out small areas. If you look closely and patiently, you see each section pulse, almost as though the earth is beating, like a human heart. Each section has its own rhythm, its own personality.

Mimicking the bubbling of sand found at a construction site, the artist asks us to consider what happens to the people who create these buildings, harmful materials seeping into their skin in much the same way that water seeps into the sand.

The pulsing of the sand was meditative, almost hypnotic. The image of the breathing sand stayed with me all day, and once I read more about the work, I couldn’t stop thinking about the way in which both these artists make us reflect on the politics and history of the basic materials they use in their art.

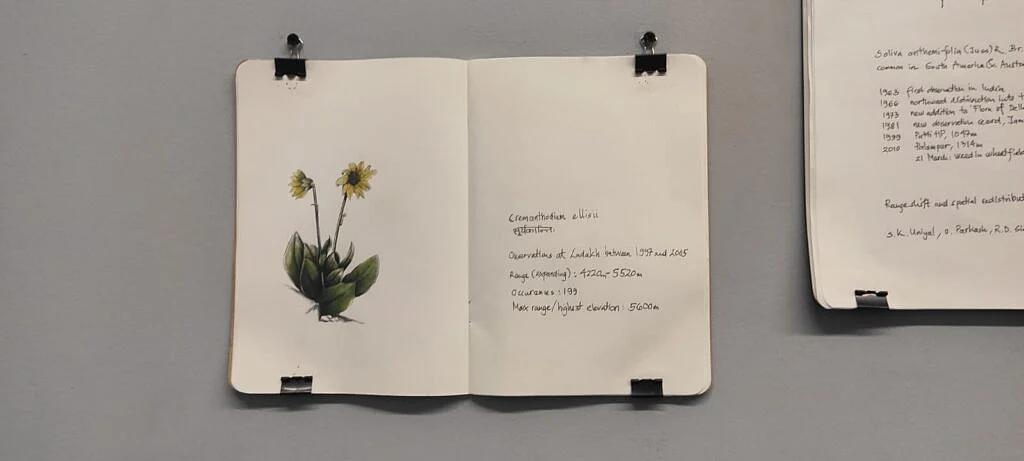

Then there was Uriel Orlow’s work, ‘Up, Up, Up’, which follows the journey of Himalayan plants. Plants that thrive in the cold, being pushed higher and higher up the slopes by global warming until there is nowhere left for them to go. Nothing can sustain them, in either direction.

I was stricken by what the artist calls ‘slow violence’. I knew, of course, about people and animals having to migrate from their homes as a result of climate change, but I had never really considered plants in the same way—they had been, in my mind, passive parts of the habitats being destroyed.

One of the works that had the most powerful effect on me was Gabrielle Goliath’s ‘The Chorus’. At one end of a darkened room ran a video of a choir, humming a single note in an endless loop. At the other end, an empty roster. Stretching in between, in a heartbreakingly tiny font, was a list of the people lost to gender-based violence in South Africa since the brutal assault and murder of Uyinene Mrwetyana in 2019. She was 19. Younger than I am now, barely older than my baby sister.

The word ‘unidentified’ occurred an unbearable number of times. The specificity of the list only reminded me further of the extent and magnitude of such violence all around the world, and how little I can do about it. Disarmed and furious, I began to hum as well. It was all I could do.

It was the least I could do. I know that some of the visceral experiences I had at the Biennale will stay with me for a long time, flooding back when I find the entry pass tucked away in a book, when I scroll through the album of photographs I took, or simply creeping up on me in a quiet, unsuspecting moment.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines