Dilli Diary: The Art of Neighbourliness

Shaunak Sen’s documentary All That Breathes (2022) becomes a paean to the art of neighbourliness.

When he was about eleven years old, Mohammad Saud rescued his first injured cheel (kite). Along with his brother Nadeem Shehzad, then about fourteen, he took the black kite to a wellknown bird hospital near their home in Delhi. The hospital refused to treat it because it was “a non-veg bird”. “That was when it hit us,” Saud says, “so what if it is a non-veg bird, does it not have a right to be treated.” Is it not worthy of being healed? The brothers were incredulous, both unable and unwilling to believe that this bird could be refused nursing, because of such a small difference.

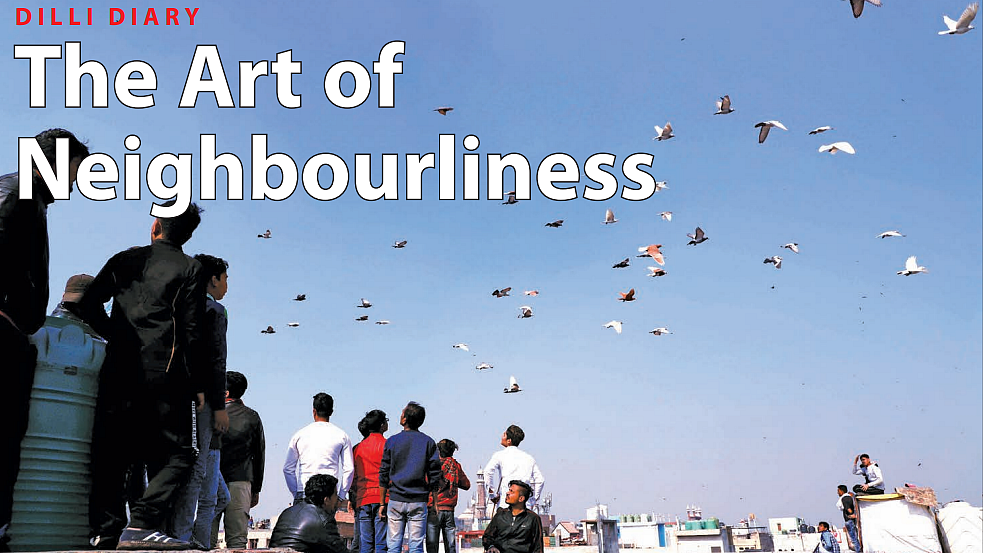

Shaunak Sen’s documentary All That Breathes (2022) follows these two brothers and their assistant Salik Rehman—who operate out of their basement bird clinic in Wazirabad in north Delhi—closely stencilling their otherworldly resilience in rescuing and treating the birds of their city, particularly the black kites, as they keep falling from its grey skies. The three years over which the film was shot coincided with the exhilarating anti-CAA protests that powerfully renewed the language of citizenship for India’s Muslims, and the gruesome anti-Muslim violence—within a stone’s throw of Saud and Nadeem’s home and clinic—that gripped north-east Delhi in the immediate aftermath of the protests in early 2020.

In more than one sense, Sen’s film becomes a paean—as magisterial as the birds that dot its exquisite frames—to the art of neighbourliness, to the contracts of empathy these three men have signed with the non-human world surrounding them. In doing so, the film quietly establishes the stakes of meaningful coexistence across all lines of difference, whether of species or of faith. Unobtrusively, with not a single pedantic word or frame, the film shores up the value of being able to see beyond the trained lines of difference, of going into the world with deliberate incredulity towards cruelty or unfairness, of seeking threads of similarity and fellow-feeling, across all the ways in which we might be, and are, dissimilar to each other. Salik, Nadeem and Saud, before they are anything else, are good neighbours to the birds.

Who (or what) are neighbours? Those who live near us. Such a simple word, but so much at stake. The neigh in neighbour is old English for nigh, or near, a word that makes us ask: who do we allow near us? The real contract of neighbourliness is always tricky, it has ethical bargains whose ends must be kept by each participant. Neighbourliness makes us ask: what do we expect from others so close to us, and perhaps more crucially, what will we allow them to expect from us? Will it only be instinctive suspicion, of those who are near us but not us, will it be a nervous, hawk-eyed alertness to what they might do the next moment, or will it be a matter-of-fact neutrality that will allow an arid sort of existence next to each other. Or, will it be neighbourliness as the scriptures tend to understand it, a form of gracious togetherness, in which we may even expect understanding and generosity from each other? In which we may, as the Gospel according to Matthew suggests, ‘Love thy neighbour as thyself ’—the form of neighbourliness in which we are ready to see ourselves in others, allow ourselves to feel what the other feels.

Halfway through All That Breathes, one of the brothers recounts, in a contemplative voiceover, a moment of tenderest empathy. Throughout his childhood, he had wondered: if he were a bird, what sort would he be? What would his beak be like, his talons, his wings, his call? And how would the city feel to him as he flew over it? In this wondering, he becomes the bird, he sees his city through its eyes, he is suspended in that feeling. Loving someone as thyself. It is difficult. Perhaps it happens so seamlessly only in childhood ruminations, in dreams… he almost instantly registers its near impossibility. No matter how much time you spend with the kite, he says, no matter how much you care for it, you cannot understand it. But you try. You take many leaps of faith.

As the brothers go about their work, the anti-CAA protests can be heard from their windows and balconies, creating a soundstage of faith and excitement. The sense of full participation in the fabric of national life slips in as a trace. The buzz of the neighbourhood shamianas and gatherings leaks into their world, and promises a vision of coexistence in which dissimilarity does not cause discrimination. In which the small differences of what we eat, which God we believe in, how we dress, whether we fly or walk, do not obliterate the fundamental likeness each of us has with the other. “Jo jo cheezein saans leti hain, unmein koi farq nahin dikhna chahiye” (One shouldn’t discriminate between all that breathes),” as Nadeem and Saud’s mother used to say. “Zindagi khud ek tarah ki rishtedaari hai” (Life itself is a form of kinship), as her sons repeat after her. Each day, unassumingly, the brothers invite their city, wracked by histories of violence and ghettoisation, into this expansive promise of neighbourliness.

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines