An Australian Diary: Looking for ‘Lijjat’ in Adelaide

Writer and teacher Ruma Chakravarti on papads and pejoratives, and the young Charles Darwin’s arrival in Sydney, Australia in 1836

We ran out of papads yesterday. As I picked up new packets of the lentil flour biscuits—for want of a better word—I thought of a brand loyalty that has lasted for over 30 years at least in my case. I also think of how the Anglicised name for these, the poppadom, is used often as a racist term for Indians, although I have seen Aussies digging into their curries using a papad as a scoop more often than I have seen my country folk do so. But then I remember the brand I am holding in my hands and I think, Come on! This is Lijjat! And some yobbo redneck calling a sub-continental person poppadom is hardly an attack on our izzat, or prestige. Being called Lijjat is like a badge of honour, like long pants or being invited to Heff's retirement orgy or something like that.

I mean, just look at the brand and its staying power. It started with an investment of ₹80 and today has a turnover of around ₹10 billion and counting. It is all about team work; teams of dough mixers, dough rollers, packers, quality testers. The list goes on and on. Quality begins firmly at home for Brand Lijjat and only those able to provide a clean kitchen to roll dough and dry it are given those duties.

Every employee is a 'ben' or sister and every employee gets paid her share in cash when the distributor comes to pick up her day's production. Only women are allowed to share in the work and the profits. These are sealed into boxes each weighing 13.6 kg. All across India the product costs the same. How do they do this and how come the Lijjat papad I have bought today will taste exactly the same as the one eaten in Calcutta 30 years ago and the one bought by a friend in Columbus, Ohio yesterday? Easy, all raw materials are bought in one place, Mumbai and then distributed from Goa to Guwahati. Every papad is made to an original recipe that is guarded proudly.

The success of Lijjat stems from its insistence on remaining a small scale operation at its very core. The number might have grown from seven women to forty three thousand women today, but the work ethic remains rooted firmly in Gandhian principles. It relies on the pride each 'ben' has in her work and her earnings, both from her work as well as her share of the profits. And like any Indian cook worth her poppadom will tell you, she will never send a less than top class dish from her kitchen into the world. In that, she and the other 'bens' are not that different from old Hugh and his dishy bunnies. Just don't go telling them that. You might get a collective rolling pinning for your cheek!

(There may be a couple of statistics wrong here, but that simply reflects on how publicity shy the brand is and of course on my rush to type this on the phone as I tidy the pantry.)

Recalling a Darwinian voyage

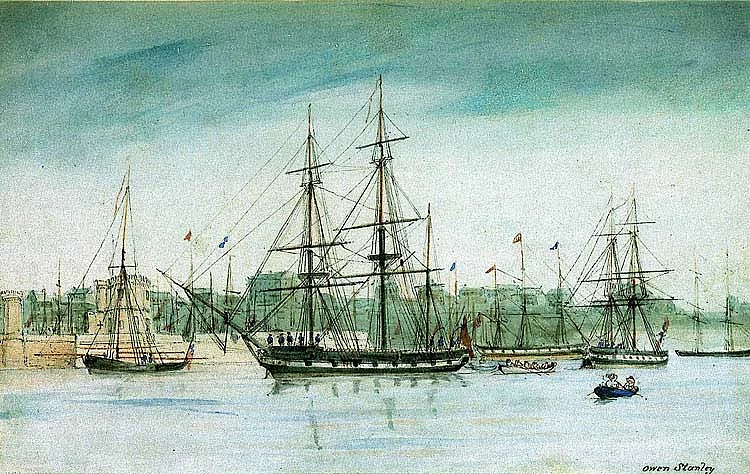

Picture this; a serious young Englishman, in the twenty seventh year of his life, on a long voyage around the world. The year was 1836. The man was planning to be a minister of the Church after his ship returned to England. But unlike the other students of religion at the time, this man was swayed from this aim by the enormous variety of life he saw on the course of his journey. Where he had started by hoping to show the power of the Almighty in creating so many forms of life, he ended up concluding that none of the complex creatures that he saw could have been created in the space of seven days. When the ship finally docked in the harbour, he was about to see animals beyond his wildest imagination. The man was Charles Darwin and the ship was the HMS Beagle. He had been on the ship for five years when it reached Sydney Harbour in the young colony of New South Wales on January 12, 1836.

Darwin had descended from a long line of scientists and his father was a doctor. Darwin, however, found the sight of blood nauseating. His disappointed father sent him to Cambridge where he studied natural sciences. His mother had passed away when he was only eight years old and the first diary entry from Sydney records that he was close to tears when he thought that he would never get any letters from her to him. Darwin recorded all the things and he saw and collected innumerable specimens of living organisms, small and large. But Darwin and indeed no one in the world could have predicted that his observations would turn the foundations of science upside down.

After spending five years travelling from England, it is not surprising that Darwin found Sydney very impressive. The city’s roads, houses and shops all met with his approval. In his diary he described the colony as ‘a most magnificent testimony to the power of the British nation’. The ever curious mind was soon keen to see what the natural landscape outside the city looked like. Like most tourists used to the green of England, he found the way to the Blue Mountains arid and unappealing. He met a group of young Aboriginal men and enjoyed interacting with them. He did, however, have concerns for their future survival, due to the fact that tribes were often at war, they were nomads, and death from diseases was common. Diseases and alcohol were two recent introductions that also had a bad effect on Aboriginal health. A hundred and eighty one years later, few may remember Darwin’s arrival in Sydney. But his predictions about evolution continue to rock the world of science.

Ruma Chakravarti is a writer and teacher based in Adelaide, Australia

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines

- Australia

- Lijjat papad

- Adelaide

- Englishman

- Charles Darwin

- HMS Beagle

- Sydney Harbour

- New South Wales

- Cambridge