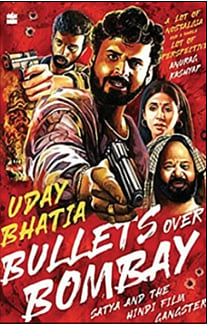

'Bullets Over Bombay': They made 'Satya' and the film made them

'Satya' triggered a new wave of gangster films in Hindi cinema. It also made Kashyap, Bajpayee, Bhardwaj and Saurabh Shukla household names. Uday Bhatia’s book brings the incredible story to life

Sriram Raghavan was a fan of (Ram Gopal) Varma long before he had seen Satya. He liked all his films – Shiva, Raat, Kshana Kshanam, Rangeela. And he’d been hearing from his friend Anurag Kashyap that this was a real gangster film, not Bollywood crap. So, when he was invited for a trial at Famous Studios in Mahalaxmi, Raghavan was more than eager to attend. He remembered the preview being full of hum jaise log (people like us).

The screening went like a dream. As soon as he got out, Raghavan bought a cigarette – he’d quit, but he suddenly felt he needed one. He shared a cab back with Tigmanshu Dhulia, who, as Shekhar Kapur’s casting in-charge on Bandit Queen, had given Manoj Bajpayee and Saurabh Shukla their starts. The two writer– directors were silent on the drive home, reliving the film in their heads.

They weren’t the only ones coming out of Satya stunned. With the kinks ironed out and the soundtrack added, the film was impressing whoever Varma showed it to. Even so, expectations among cast and crew were tempered. As everyone kept reminding them, you needed stars to open big, and they only had one (you also needed songs, and fortuitously, Vishal’s music was catching on, especially the boisterous ‘Goli Maar Bheje Mein’ and ‘Sapne Mein Milti Hai’). Those were the days when hit films ran for months. If Satya folded in a week or two, it probably wouldn’t recover its costs.

Kashyap, Bajpayee, Sushant Singh and Kamran had moved on to Varma’s next, the home invasion thriller Kaun. As Satya’s release drew near, how often did their discussions turn to the film’s chances and the fallout of possible failure? They all thought they’d pulled off something special, but who could tell? Is Raat Ki Subah Nahin, for all its critical acclaim two years earlier, had sunk without a trace.

Sriram called his brother after the trial screening of Satya and said, ‘Boss, I’ve seen one of the deadliest movies ever. I’ll book tickets for us.’ He was expecting a ‘houseful’ sign when he turned up for the first-day show on Friday morning at Anupam Cinema in Goregaon. Instead, there was hardly anyone outside the hall or crowding the ticket window, let alone touts selling in ‘black’. He came away worried for the film’s chances.

Satya opened on 3 July 1998, at a less-than-encouraging 50 per cent capacity. In those days, films generally weren’t pulled from theatres in a hurry as they often are now. Nevertheless, Bajpayee felt the onset of panic – after all that hard work, he was back to square one. Outside Shaan theatre in Vile Parle, he met Ajit Dewani, who told him, ‘Teri film flop ho gayi, doosri film jaake khoj’ (Your film is a flop, go find a new one).

Varma remembered trade analysts writing off his chances – good film, but too intelligent, too intense. Bharat Shah called him on the first night, saying, ‘Thoda disappointing hai, dekhte hain’ (It’s a little disappointing, but let’s see what happens). The following night, Varma got another call. This time, Shah was excited. ‘Ramu, bol rahe hain ki picture utaregi nahin’ (They’re saying the film won’t be taken off).

‘I had zero expectations,’ Kashyap said. ‘I remember, first week was some 60–70 per cent occupancy. This went up to 90. Third week was 97. Then it was houseful. I was thinking, what the f… is going on?’ Kamran recalled a couple of them piling into Varma’s car and driving from the suburbs to Churchgate, staring in amazement at one full house after another.

The gang wasn’t sweating now. Instead, for the first time in their lives, they were getting recognised. Bajpayee heard ‘Bheekubhai, Bheekubhai’ wherever he went. Sometimes, people would come up and speak to him in Marathi, figuring he knew the language; he’d figure out the gist and reply with the few phrases he knew. Shukla got used to being called Kallu Mama by strangers (it’s ‘dark-skinned uncle’ in Hindi). Doors they’d never dream of knocking on earlier were now miraculously open.

Outside a washroom at a movie theatre, a few vodkas down, Bajpayee met his childhood hero, Amitabh Bachchan (‘There was some ringing sound in my ears,’ he recalled). Kashyap related a similar story. A frantic search party cornered him at a studio, saying Bachchan was on the phone. ‘Literally, my hands were shivering. I took the call. His first line I remember: “Atal Bihari ko dhoondna aasaan hai, aapko dhoondna bada mushkil hai” (Tracking down Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee is easy, finding you is very tough).’

A couple of months earlier, Chakravarthy was in the edit room when Varma gave a peek of his film to a mystery guest. Sitting in a corner of the dark studio, Chakravarthy listened to the man praise the scenes and wondered why he sounded so familiar. ‘One thing, though, Ramu,’ the voice continued. ‘Why did you cast the South Indian actor? You should have taken someone from here. If the film doesn’t do well, it’ll be because of him.’ In that terrible moment, Chakravarthy realised the speaker was Anil Kapoor.

Sometime after the release of Satya, Kapoor was in Hyderabad for a film shoot. Chakravarthy happened to be in the same studio, and went to pay his respects. He was surprised when Kapoor jumped up and hugged him. ‘Kya kaam kiya!’ (Excellent work!), the Mr. India star said. ‘When I was shown your scenes, I told Ramu, if the film does well, it will be because of this guy.’

Some of the most enthusiastic reactions came from those who saw their rough lives playing out on the big screen. At one screening, Kamran and Bajpayee were approached during the interval by a tough-looking group. ‘These guys came up – surely underworld people from the chawls,’ Kamran recalled. ‘They told Manoj, kya kaam kiya, phaad dala (great work, you tore it up). They talked to him like he was a bhai. I’ll never forget that moment. You make a film, and the actual people from this life confront you.’ On another occasion, outside a different theatre, a stranger put his hand on Varma’s shoulder and said, ‘Hum logon ke upar acchi picture banaya hai tu’ (You’ve made a fine film about people like us).

Film journalist Anupama Chopra had yet another story. ‘Pappu Nayak is an underworld foot soldier,’ she wrote in India Today, two months after the film’s release. ‘Solidly built, he walks with a swagger in Goregaon, Mumbai. Ostensibly he works in a dairy but actually he’s the local fixer, working with fists and choppers, settling disputes, extorting money and fixing elections. Last Sunday, Nayak saw Satya. For the fourth time. “Boley to, bahut real story bataya hai,” he says. “Bheeku Mhatre ke liye char baar dekha. Wo ladka agar ek do film mein jum jaaye to Nana Patekar ko thanda kar dega” (They’ve told it the way it is. I saw it four times for Bheeku Mhatre. If that guy does well in a few films, he’ll put an end to Nana Patekar).’

(Excerpted with permission from 'Bullets over Bombay: Satya and the Hindi Film Gangster' by Uday Bhatia published by HarperCollins Publishers India)

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines