Book extract: The Eternal Outsider

Bhanwar Meghwanshi’s memoir is a powerful document that blows the lid off the Sangh’s appropriating instincts and its supposed Dalit outreach

Sometime after returning from karseva, around May or June 1990, I expressed to the district pracharak, Shivji bhaisahab from Jodhpur, my desire to become a full-time pracharak, giving up family and home, leading the life of an ascetic dedicated to the nation. He gave me a very long reply, of which two things he said are engraved in my memory.

Me: Bhaisahab, I want to become a pracharak.

District Pracharak: Brother, your ideals are indeed very high-minded. But you have to see the broader picture. It’s all very well that you’re excited about becoming a pracharak, but our society is very complicated. Tomorrow, someone asks you your name, your village, your samaj [he said community, but meant my caste], and the moment he realises that pracharakji is from a marginalised community, his attitude to you might change. You would have to swallow the insult. I can see this and it’s why I’m telling you. You will be upset, want to retaliate. Arguments will follow. All this will weaken the work of the Sangh, not strengthen it. My advice is to remain a vistarak for a while and serve the nation in that capacity.

I was devastated by his reply. I felt intense pain at having been born in a lower caste community. But how was this my fault? What a predicament for me—here I was, ready to sacrifice my life for the sacred work of the Sangh, but my caste over which I had no control was proving an obstacle. I gradually came around to accepting it, consoling myself that while Hindu society was not yet ready to accept me, the Sangh was relentless in its attempts to bring about the transformation that would end all hierarchy. Soon the time would come when even one such as I, from a lower caste, would be able to work full-time for the nation as a pracharak. Meanwhile, even before this conversation, I had begun to write. At first there were fiercely nationalist poems. I also brought out an issue of the handwritten magazine Hindu Kesari, titled ‘Annihilate Pakistan’. I then began to write columns on nationalist thought in local newspapers. I would go to shakhas in my ganvesh and conduct the intellectual sessions. I lost no opportunity to build myself up as a Hinduvaadi, champion of the Hindu cause. But somehow, I felt I was not being accepted the way I wanted to be, as was my right, given all my work.

In the conversation about becoming a pracharak, another thing was said that really showed me my place. Mocking my intellectual work, pracharakji indicated my head and said: “You people who think too much, you’re just strong above the neck, not physically. In any case, what the Sangh needs is a pracharak who can convey the message from Nagpur exactly as it was intended, to Hindu society. We don’t really want people like you, vicharaks, who are constantly questioning and thinking.” And thus my thinking (vichar) made me unfit for the job of propagating the thought of the Sangh (prachar).

You have to understand that the system of pracharaks is the very spine of the Sangh, these are men who have sacrificed everything, all family life, for the cause. One RSS leaflet I consulted states that there are 2,559 pracharaks, of whom 1,646 are for shakha work, 147 for organisational work, 437 for work in Sangh-related bodies, and 335 vistaraks for starting work in new areas. Such figures are released from time to time by the RSS, but they keep changing, because new pracharaks join, others pass away; vistaraks are appointed for limited periods, some of them return home, and so on. The RSS does not make public any consolidated figures about its pracharaks and vistaraks, although scattered information reaches the media on and off.

…

Towards Ambedkarism

I returned to my village in August 1995. Now I was more inclined to make a political response. The Dalit–Muslim alliance had failed to take off, and Christianity turned out to be not at all different from Hinduism. It seemed all religions were equally rigid and irrational. On the surface it was all sarva dharma sambhava—treat all religions equally—but actually every religion had a secret agenda to expand its followers and control the world. Some wanted to make the whole world dar-ul-Islam, subject to the laws of Islam; while others were insistent upon sharing the gospel with one and all. As for Hindus, they were no better. Declaring krinvanto vishvam aryam (‘Let us Aryanise the world’, meaning, elevate it), the Rig Vedic verse made popular by Dayanand Saraswati as the motto of the Arya Samaj, they were bent upon ‘civilising’ the world. Each one expansionist, each conjuring visions of heaven and hell. I wanted to run far away from the abstractions of fear, fortune and god.

So I started searching for alternative writings, and started with Ambedkar’s works. Until now, I knew of Ambedkar in two ways. First was through the RSS, where in every morning prayer at the shakha we remembered Ambedkar. I had also read the Sangh-approved story of his life written by Dattopant Thengadi. Second was through my reading of Osho, where Gandhi was criticised and Ambedkar counterposed to him as the more scientific and rational thinker.

I had read about Babasaheb Ambedkar here and there in Sangh publications like Panchjanya, Pathey Kan, Rashtra Dharma and Jahnavi, from which I learnt that Babasaheb was a great nationalist, and had contributed to writing the Constitution of India. That he had wanted to make Sanskrit the national language and the saffron flag the national flag. That despite every temptation, he had not converted to Islam or Christianity but to Buddhism, which was part of Hinduism. And that he was opposed to the continuation of Article 370 in Kashmir, which gave the state a special status.

Now I was reading Ambedkar himself, and found that his views on everything were the exact opposite of what the Sangh claimed. It was the first time I was reading him directly, not as presented by the Sangh. I was dumbstruck. The first book I read, Riddles in Hinduism, blew my mind. After that I found everything I could that Babasaheb had written. I learnt about the many bitter circumstances that arose in his life, with which he had to deal. Annihilation of Caste gave me a clear understanding of how Brahminism was responsible for the establishment of the hateful system of caste hierarchy and discrimination. I came to recognise the true nature of the RSS. How, through their claim of samrasta or harmony, they were subverting the possibility of equality, justice and social transformation. And what the politics was behind naming Dalits as neglected (vanchit) and Adivasis as forest dwellers (vanvasi), denying us our own identity. I was now horrified by the song we sang routinely in the shakha—Manushya tu bada mahan hai/ tu Manu ki santan hai (Man, greatness is your destiny/ You are Manu’s progeny). The song celebrated humans as the offspring of Manu—the very Manu who had enforced the system of caste hierarchy in the well-known Manusmriti, who considered Shudras, women and avarna untouchables as less than animals. Such a person was being celebrated as a great sage and the ancestor of all humans? What could be more evil?

The closed doors of my mind had started opening up. I read the Manusmriti and realised that Babasaheb was right. The treatise should be burnt as Babasaheb had done in 1927 in Mahad. As I read more and more of Babasaheb, the more my rebellious thoughts took firmer shape. Ambedkar’s writings sowed the seed of progressive thinking in me. A Dalit perspective helped me understand my personal, individual struggle against the Sangh as a collective struggle for identity, social justice and dignity.

Then I read Kabir, Periyar and Phule. I was no longer just a rebel. My desire for revenge was slowly becoming a desire for transformation. In place of the poetry I had written for my own pleasure and for the entertainment of others, suddenly emerged poems that raised burning questions. I burnt my old romantic poems, full of metaphors about beautiful dusky locks of hair and deep intoxicating eyes.

Now the mood of my poetry was rebellious. I wrote:

Burning just the Manusmriti,

Why did you stop at that, Babasaheb?

Why didn’t you burn

All those volumes in which Manu

resides,

In the minds of the so-called uppers….

And about Ekalavya’s devotion to his teacher:

Why Ekalavya, did you sacrifice

As a gift to your teacher, your thumb?

Why didn’t you cut off

Dronacharya’s head,

So that no other Ekalavya

Should be asked to give up his thumb

By another Drona,

And never would be born

Ever again, those who follow Drona….

On Ram and Sabari:

Raja Ramachandra,

You did not leave

With that Adivasi woman Sabari

Even a half-eaten fruit,

And you too kept faith

With enmity against us.

Those days I wrote dozens of verses like this. The tone of my prose writing changed too, turned revolutionary. In place of abstract supposedly literary stories, emerged sharp, rough, troubling stories about Dalit life and oppression and struggle

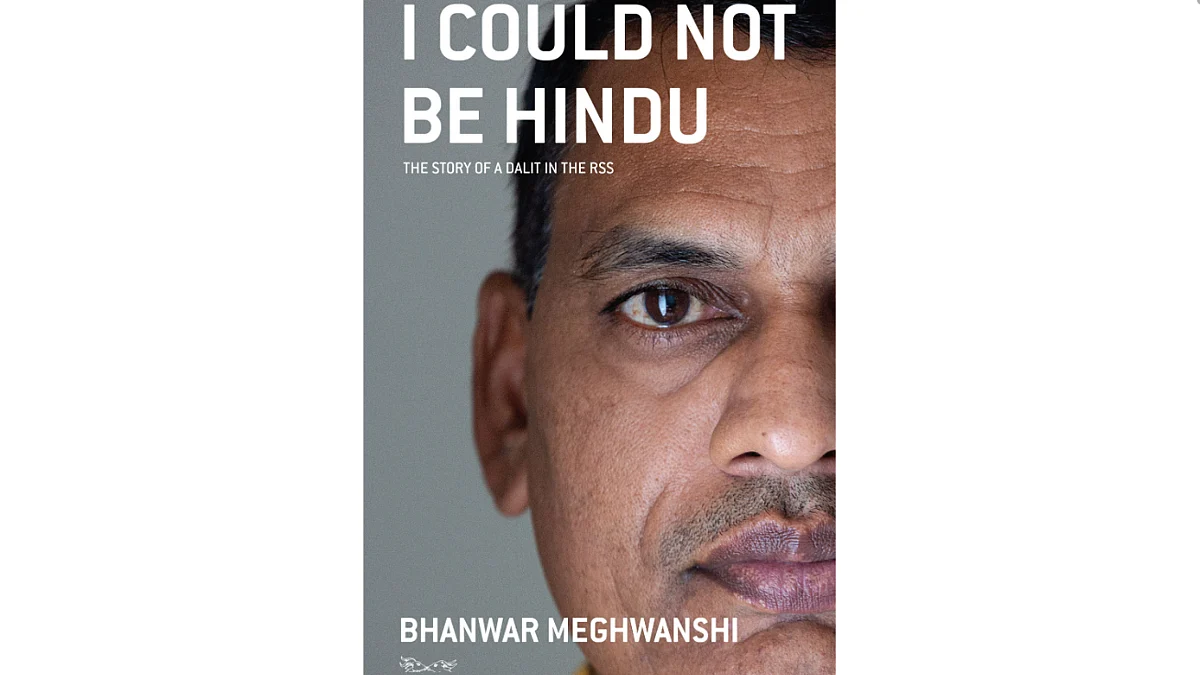

Extracted with permission from I Could Not Be Hindu, Navayana, 2020

Follow us on: Facebook, Twitter, Google News, Instagram

Join our official telegram channel (@nationalherald) and stay updated with the latest headlines